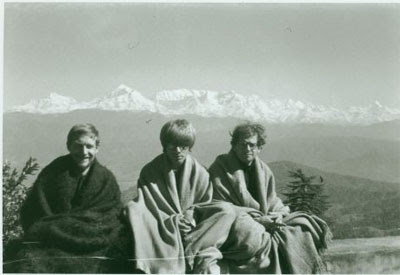

Gary Snyder: Photo Arya Degenhardt: Mono Lake Community

Who can leap the world ties/and sit with

me amongst the white clouds

Han

Shan,a Tang Dynasty poet.

Almost half a century ago, I was walking back

to Camp 4 in the Yosemite Valley, accompanied by the legendary US climber,

Chuck Pratt, when we met up with another outdoor enthusiast walking in our

opposite direction. This stranger, unknown to me, was known to Chuck, and they

exchanged greetings, and I was introduced in that off hand way that climbers

think of as sufficient, and we went on our way, eager to reach camp and slake

our thirst after a day, climbing in the intense heat of August.

Once back in camp, I ventured to ask Chuck

who the guy we had met earlier was, ‘Oh he is from California University. Many

years ago he worked here in the Park trail-building. So he knows a lot about

Yosemite and Its history’. I had only heard that his name was Gary in our

introduction, and it was some time later that I realised that this was Snyder,

one of the most famous writers in the States, already with a legendary back

story, and a mountaineer of some experience beginning with a very youthful

initiation into the sport.

I had been introduced to his writings by one

of my own mentors also when young, the late Harold Drasdo. Who in one of our

discussions bivouacking under Castle Rock in the Lake District, had enthused

about an essay he had recently read by Gary Snyder about hitch-hiking. As it

was at that date our own mode of transport, this was what had caused him to

take up on this work, and he opined that ‘it was the best such piece of writing

he had ever read about the activity and he recommended me to read it!’ High

praise indeed for Harold had a keen critical eye for such literature.

He was born in the San Francisco area in

1930, but moved as a schoolboy to Oregon at the break-up of his Parents marriage;

whence he started with other school friends travelling out into the countryside,

and then as a young teenager he started to climb. He joined the Mazamas

mountaineering club, based in Portland where he went to school and eventually

college and over the next immediate years he ascended many of the major peaks

in the Cascade Mountains, Mounts Hood, Baker, Rainier, Shasta, Adams, and St

Helens.

Descending off the last as a 15 year old he learnt with some horror of the dropping of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. By the time he was 20 years old he was a highly experienced mountaineer, but his ascents were accomplished with a brio where he wished ‘to develop a fresh mountaineering mind-set that was totally opposed to the notion of conquest. I and the circle I climbed with were extremely critical of what we saw as the hostile Jock, occidental mind-set which was to conquer it…… I always thought of mountaineering not as a matter of conquering the mountain, but as a matter of self-knowledge’. He went on to also note ‘that my first interest in writing poetry came from the experience of mountaineering. I couldn’t find any other way to talk about it’. Only someone who has climbed could write a poem like the following;

After scanning its face again and again

I began to scale it, picking my holds

With intense caution. About half-way

To the top, I was suddenly brought to

A dead stop, with arms outspread

Clinging close to the face of the rock

Unable to move hand or foot

Either up or down. My doom

Appeared fixed. I must fall

Descending off the last as a 15 year old he learnt with some horror of the dropping of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. By the time he was 20 years old he was a highly experienced mountaineer, but his ascents were accomplished with a brio where he wished ‘to develop a fresh mountaineering mind-set that was totally opposed to the notion of conquest. I and the circle I climbed with were extremely critical of what we saw as the hostile Jock, occidental mind-set which was to conquer it…… I always thought of mountaineering not as a matter of conquering the mountain, but as a matter of self-knowledge’. He went on to also note ‘that my first interest in writing poetry came from the experience of mountaineering. I couldn’t find any other way to talk about it’. Only someone who has climbed could write a poem like the following;

After scanning its face again and again

I began to scale it, picking my holds

With intense caution. About half-way

To the top, I was suddenly brought to

A dead stop, with arms outspread

Clinging close to the face of the rock

Unable to move hand or foot

Either up or down. My doom

Appeared fixed. I must fall

(An extract from a longer poem, ‘John Muir

on Mount Ritter’)

Snyder studied Literature and Anthropology

at College, and became interested in folk lore research, and spent some time at

the Warm Springs Indian Reservation in Central Oregon. This experience was to

be a major influence upon him, drawing on their songs and poems and feelings

about nature and mountain scenery. This was also the beginning of an interest

in Buddhism, particularly because of its attitudes pro nature, and each winter

there was also mountain skiing. He ran around with a group of older ex-ski

troopers, who called themselves ‘The Wolken-Schiebers’.

Spring water in the green creek is clear

Moonlight on Cold Mountain is white

Silent knowledge-The spirit is enlightened of itself

Contemplate the void: This world exceeds stillness.

It was in the summer of 1953 that Snyder

and Kerouac worked as fire Lookouts, and this is now the subject of a coffee

table book of photographs and text by John Suiter, ‘Poets on the Peaks’

published in 2002. Snyder’s Lookout was on Sourdough Mountain, and Kerouac’s

Desolation. One feels reading about this now that the latter took some

persuading to take this on, but was converted to the idea by Snyder’s mantra,

that ‘the twin of the active life is the contemplative one’ and as a fire lookout

for six weeks one has many hours in which to undertake this! As Snyder wrote as

he left his peak…..

I the poet Gary Snyder

Stayed six weeks in fifty-three

On this ridge and on this rock

And saw what every Lookout sees

Saw these mountains shift about

And end up on the ocean floor

Saw the wind and waters break

The branched deer, the eagle eye

And when pray tell, shall the Lookouts die.

Amazingly now Snyder’s activities as a

poet interested in Chinese studies, and working as a lookout in the summer months,

brought him to the attention of the infamous senator Joe McCarthy, head of The

House, un-American activities committee. And he was blackballed for not being

patriotic enough to work any longer for the US government as a Lookout. At

least he was in good company over this for many of the most outstanding artists

and writers of that era suffered a similar fate, everyone from the playwright

Arthur Miller to Charlie Chaplin.Stayed six weeks in fifty-three

On this ridge and on this rock

And saw what every Lookout sees

Saw these mountains shift about

And end up on the ocean floor

Saw the wind and waters break

The branched deer, the eagle eye

And when pray tell, shall the Lookouts die.

I never was so broke and down

Got fired that day by the USA

(The district ranger up at Packwood

Thought the wobblies had been dead for forty years

But the FBI smelled treason-my red beard

The literary fame of the Beat poets was

launched in October 1955 at a reading in the 6 Gallery in San Francisco, and

whilst it is Ginsberg’s long poem ‘Howl’ that is best remembered, Snyder’s

follow on contribution ‘The Berry Feast’ has also stood the test of time. Most

of the Beats were enamored of Eastern religion and psychedelia (way ahead of groups like The Beatles and

other popular artists of the ‘sixties) and for Snyder it was Zen Buddhism that

was to be his spiritual muse. Zen is a fusion of Mahayana Buddhism and Taoism.

This latter a purely Chinese construct as is Zen which is known in China as

Chan. Bidding goodbye to the Beat poets, he took off in 1956 for Japan, where

he enrolled at a monastery in Kyoto to study Zen, but also to continue his

writing and translating poetry. His 1957 collection of poems ‘The Back Country’

also includes translations by him of the now famous Japanese poet Kenji (1896-1933).

He stayed in Japan until 1964, and then returned home to the USA as a crew

member on an oil freighter.

It comes blundering over the

Boulders at night, it stays

Frightened outside the

Range of my camp fire

I go to meet it at the

Edge of the light.

A short finishing poem perhaps sums up

best how he feels about the wilderness experience:

For All.

‘Ah to be aliveOn a mid-September morn

Fording a stream

Barefoot, pants rolled up

Holding boots, pack on

Sunshine, ice in the shallows

Northern Rockies.’

Dennis Gray:2015