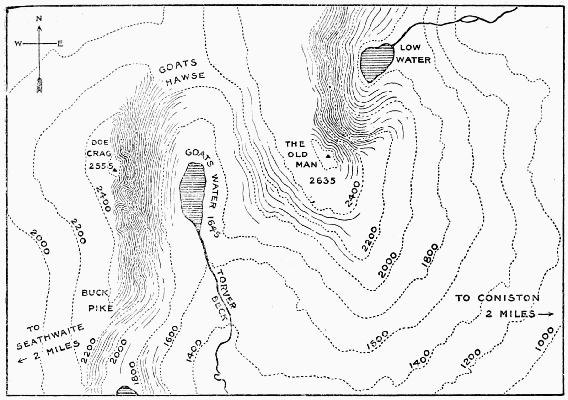

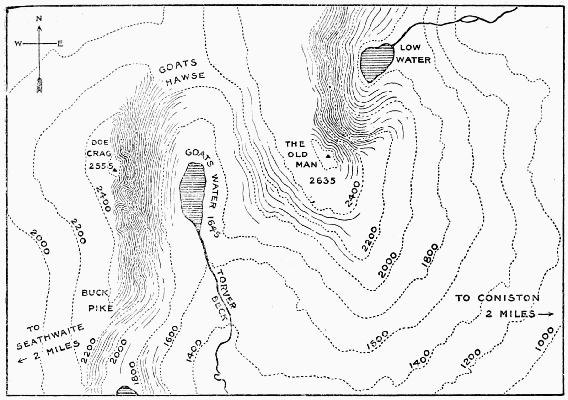

Coniston Fells: Original painting-Delmar Harmood-Banner 1938

Arthritis Cottage,

Ambleside,

Cumbria.

Dear Jeanette,

I am sorry...I apologise. I feel desolate. I did not mean to

make you unhappy with what I said about your soloing Hopkinson’s Crack on Dow

Crag. I never imagined you would flounce out of the climbing shop as you did,

slamming the door and making us squirm with embarrassment. We Brits dislike

scenes. I was clearly the culprit. “She didn’t like that,” said Julia,wrapping

a pair of Huecos at the till. No, clearly you didn’t. Yet I had meant well.

Jeanette is, of course, no more your name than Arthritis

Cottage is my address. But you know me - or should do by now. (When was it we

last climbed together on Dow- 1953 ? I simply can’t take things seriously. But

I feel serious enough to want to protect your identity as I try to make up for

my calamitous mistake. In those days Dow Crag was a giant place. Still is: an

eyrie of the mountain gods; its ramparts the kind that make the climber’s heart

skip a beat when seen from deep in the valley near Torver, or high on the

footpath from Coniston. The times our bunch from Ladnek had on Dow! Was there

ever a dull moment? Unlike today where the po-faced reign.

So you see, Jeanette, my memories are fond ones, treasured

from an age ago when everything was sunlight and laughter, when you were a

leading light. You in your shorts and long brown legs, joyfully and

outrageously- for that time - soloing Hopkinson’s Crack. When I introduced you

to Julia thus, I was re-living my golden and most affectionate moments of

climbing innocence.

Your angry rejoinder that “Tony may live in the past but I

prefer to live in the present!”, not to mention your double-quick exit through

the door - saddened me utterly. Everyone looked so accusingly at me. Perhaps

Jeanette, for all your success as head one of the biggest British branches of

an international organisation, you regret that you’re no longer climbing.

Possibly it’s too painful to bring back those days when your hair was a cap of

blondest curls and when the sun blazed like a blowtorch, heating the rock on

which you smeared so daringly in your Woolworth’s rubbers. If that is the case,

then is it any wonder my words struck such a painful chord?

Hopkinson’s Crack rockets into the air from the depths of

the Amphitheatre – an unusual feature for Dow, where many routes climb exposed

battlements, busy with climbers at weekends. How different is the setting for

those solos of Hoppy’s you did! Grim, silent walls surround you on either side.

Just to reach the foot of the crack seemed an expedition, about that time when

Everest was climbed, as we cranked fearfully up into the Amphitheatre past the

massive boulder jammed in Easter Gully; or instead descended into its

bottomless pit from the steep end of Easy Terrace, tricounis grating on wet rock.

The situation of Hopkinson’s Crack graded Hard Severe but

verging on VS – is galactic. On the left is the mendacious pillar of Great

Central Route, while on the right is Black Wall. How your heart must have raced

when soloing: especially when you drew level with the small rock stance and the

crux of Hopkinson’s loomed overhead.

You were climbing a deep cleft until then, but at this point

your world fell away. I seem to remember you climbed the right wall, heart

stopping in its exposure. The alternative is to climb the crack, bridging occasionally,

reaching and reaching again, up past the big hex that fits so snugly in the back,

to where many (including me) make an inglorious landing on the Bandstand.

Climbing solo though, you bypassed this famous haven and

continued straight on up the crack, the next pitch an arrow-straight skyshot

offering bridging that is exquisite. Is it surprising, therefore, you might now

regret no longer doing what you once did with such elan and such prowess?

In those days,Jeanette, routes like Eliminate A and Murray’s

Direct were a world away. But possibly you went on to do both before you hung

up your rubbers and wet day socks. I sincerely hope so, for they are also quite

magical. I climbed them first in the 1960’s. But they are the kind of routes

you would so enjoy: the best sort in the world. Eliminate A, to start with,

pierces the front of the great buttress on the left, its bigness on a par with

that of Notre Dame. A smooth wall is shaded by a slanting roof, continuing

above like a great rock prow. That any VS can breach its front is unthinkable. Yet

Eliminate A does just that, with four particularly memorable pitches. The first

runs out 90 feet of rope above the depths of Great Gully, leering up at the

intrepid leader engrossed in placing his gear; layaways and rockovers, the kind

at which you used to excel, dear Jeanette, coming at you faster than you can

stop them.

The shelf below the Rochers Perchers pitch arrives as a

welcome refuge, but the take-off up the next mauvais pas comes as a shock; so overhung you stay dry in the rain,

you are soon above a chuteful of thin air. Here is where Neil Allinson felt

himself slipping down the crag and

realised the block he was pulling on ( one of the heavy Rochers Perchers

themselves) was slowly sliding down towards him. Have you met Neil? He’s the

coal miner who inadvertently pulled the Rochers Perches off; said it was like

the pit roof coming down in Eldon Drift Colliery, Co. Durham.

The third of Eliminate A’s great pitches is the next one,

slanting up leftwards beneath the great roof and using the edge of a crack as a

handrail, made all the more enthralling for its lack of gear especially as you

pull through and over onto the steep slab above - which is the fourth pitch of

note. And what an immaculate pitch it is! A rising traverse on the very lip of

the roof which has shadowed you for so long, with nothing but outer space

below.

On you climb, up and up past the steepest rock, with holds

and runners always coming. There’s a further pitch above, but it’s difficult to

trace. The crack of Aréte, Chimney and Crack is a popular finish however.And

then Murray’s Direct, the third of this trio of three-star routes. Then, when we

used to stash our Bergen sacks under the cave on the scree, bouldering on the nail-worn

slab immediately behind (4b today), I never dreamed that one day I, too would

climb the inexorably smooth slab of Tiger Traverse - let alone the imperial

line above: a magnificent corner hooded by overhangs and the essence of

perpendicularity. Yet that is Murray’s Direct.

The Tiger Traverse slab is so tilted, the climber feels about

to be tipped off onto the horrific landing below, gnarly jagged rocks and all.

But wait. Today’s gear saves the day. Wires and Friends fit into a horizontal break

immediately above the step up from a pointed flake, the next moves up and away

also being protected by a further placement before the padding starts. Then happy

holds are here again.

Tiger Traverse over, the open-book corner above is

positively inviting. There are beautiful

holds for bridging; everything is so steep. But this is only the link pitch.

The crux is still above, the corner itself deepening and cowled with overhangs. Glance down between

your legs as you bridge out above the tiny stance and it’s spit-straight to the

screes. Then the immediate climbing has all your attention. Is it a layback, or

a jamming crack, or will you bridge it as well? So near the belay, yet so

wonderfully poised in such an outlandish position, it has seen the drying of

the saliva glands inside many a leader’s mouth - that sure symptom of apprehension.

No spitting now: at least not until relief once more flows through the body as you

bridge and bridge again to reach better holds and begin to feel you are

winning.

Shielded from the sun after mid-day but bathed in it before,

Murray’s Direct is a well-protected line, complementing superbly both Eliminate

A and, dear Jeanette, that climb I always associate with you, Hopkinson’s

Crack. Whether you ever return to the rock or not (and surely it’s never too

late, looking as fit as you do) I can

only wish you the very best. And hope you will now realise that whenever I

might have so innocently gone on about Hopkinson’s

in the past, I saw it as a landmark to cherish rather than the reverse. A

beacon in the light as the years roll by. We all need them.

Take care then,

Jeanette. Fight gravity in all its insidious

forms. There are so many straight faces around today, not to mention individuals

with independent “miens”. Wherever did light-heartedness go?

All love and best wishes,

Yours affectionately,

Antonio (and his ice cream kart).

Antonio Frascarti:First published in Climber April 1992

.jpg)