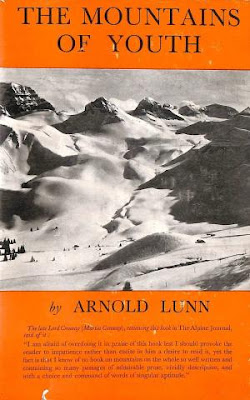

Dduallt: Looking out towards the Arans

It was late one night,

as I was re-checking the galley proofs of the seventy-eight chapters

making up Classic Walks, when the phone rang. Jim Perrin was on the

line. "Get out the Dolgellau O.S. map and look at the huge tract

of mountain country between the Arenigs and the Mawddach Estuary. A

walk linking the Migneint in the north with Cader Idris in the south,

including Arenig Fawr, Moel Llyfnant and Rhobell Fawr would have a

quintessentially Welsh flavour with all the beauties, problems and

archetypal character of that country." Any recommendation from

Jim is good enough for me and I hastily agreed to the last minute

addition. Ken Wilson used all his persuasive powers to get Jim to

extend his walk to a marathon crossing of the hills from Blaenau

Ffestiniog to Dolgellau over Manod Mawr, the Migneint, the Arenigs,

Moel Llyfnant, Dduallt and Rhobell Fawr. But Jim was spared —

merit, not severity was our guideline, I reasoned, and anyway, the

Migneint and Arenig Fach had already been admirably dealt with by

Harold Drasdo.

Jim's manuscript duly arrived and I read it with more

than usual interest for I was not well acquainted with the area. My

interest quickened even more when I read that Jim rated Rhobell Fawr

his favourite Welsh mountain. This made it an exceptional hill for,

as readers know, Jim is a most discerning and sensitive commentator

on the topography of North Wales and he knows every cwm, llyn and dol

in the Principality. Rhobell Fawr leapfrogged to the very top of my

list of hills to be climbed and the first opportunity arose one day

in early June. North Wales was suffering a heat wave and I planned my

day very carefully. No thirty mile marathon of sweat and aching

limbs; a mere fifteen mile hill crossing from Llanuwchllyn to

Dolgellau would give me Dduallt and Rhobell Fawr followed by a gentle

descent to the Mawddach. The morning was deliciously cool as, at 5.45

a.m., I left Dolhendre on the Llanuwchllyn to Trawsfynydd road and

made for the hills. Whilst crossing the Afon Lliw a heron flapped

loosely overhead. A good farm track leads south of the rocky bluff,

Castell Carndochan, and then an indistinct path winds up through the

pastures, between twisted rowans and tumbled-down walls, now

overgrown and thick with moss.

The fields were bright with harebells

and heath bedstraw and my feet left a track through the dew. After

half an hour the path petered out and the hillside was rough with

tussocky grass, bilberry and deep heather. I paused for a moment

under a line of rock outcrops falling away on the south side of Craig

y Llestri and looked about. Rolling mists clung to the valleys below

and completely covered Bala Lake but, rising well above the mist and

already bathed in sunshine, ran the long line of the Arans. The view

north was dominated by the shapely profiles of Craig y Bychan and

Moel Llyfnant, while to the west Dduallt, my first objective, rose

abruptly from the flat moorland belying its 2,153 feet. From the east

Dduallt appears as a long whaleback, ribboned by buttresses of grey

rock, and I altered course to make for the north ridge, the natural

route of ascent. The high, open plateau under Dduallt has recently

been fenced and drained and I suspect the conifers, at present just

visible topping the ridge to the south, will soon be marching on

towards Dduallt itself. From a distance the drained area appeared

white with what I suspected to be lime but turned out to be cotton

grass.

Rhobell y Big Summit

My eye caught a glint in the heather and I picked up a tiny

metal ring bearing a code number. It was the identity ring of a

homing pigeon and a local fancier traced the owner to Ballymena, Co.

Antrim. The pigeon had been released from Haverfordwest in 1980 and

had almost certainly fallen prey to a peregrine falcon. From the

increasing number of birds lost, pigeon fanciers reckon that the

peregrine population in Wales is multiplying. The north ridge of

Dduallt is quite broad, but always interesting with rock outcrops to

be negotiated and ever widening views west to the Rhinogs and south

to Rhobell Fawr. Ragged grey clouds hung over the Rhinogs but it was

only 8.00 a.m and the sun's warmth had hardly taken effect. The way

ahead to Rhobell Fawr was blocked by a huge forestry plantation

filling the valley on the west side. The 1974 Landranger map showed a

gap in the trees on the south side but this too had now been planted.

However, from my bird's-eye view I could see an obvious broad

fire-break leading in the general direction of Rhobell Fawr and I

made for this. The forest was not as impenetrable as it looked from

above because rocky ground prevents close packing of trees, unlike

some of the dense Northumbrian forests, I was intrigued to see the

smaller fire-breaks had recently been planted with cupressus.

The

Forestry Commission now realises that most fire-breaks are useless

and they are filling them in with fast growing crops like cupressus.

It was a relief to emerge from the trees high up on the north

shoulder of Rhobell Fawr, where Welsh sheep were grazing the close

cropped grass between the rock outcrops. The ewes and their lambs

ignored me and I thought what clean and peaceful creatures these

Welsh sheep are, an altogether superior breed to the nervous and

scraggy Swaledales and Scottish Blackfaces of the north. Jim Perrin

talks of a tame fox on Dduallt. I did not see it but I was rewarded

by the sight of a young fox, with a white tip to his tail, watching

me until, when I was within ten metres, he turned and slipped away

into the rocks. Rhobell Fawr is virtually unknown and not a vestige

of a path scars its upper slopes. The O.S. pillar at 2,408 feet is

tastefully constructed of natural stone and in no way intrudes on the

landscape. I sat down for a second breakfast by the pillar at 9.45

a.m. and although the sun had not quite dried the dew on the grass it

was quickly evaporating the clouds on the Rhinogs and Cader Idris.

The three sheets of water visible to me, namely Lake Bala, Lake

Trawsfynydd and the MawdachEstuary were beginning to sparkle. Set

in an unfashionable tract of mountain country and hardly worth

climbing for their modest heights alone, Dduallt and Rhobell Fawr are

ringed by the popular ranges, Snowdonia and the Moelwyns to the

north, Cader Idris to the south, the Rhinogs to the west and the

Arans to the east. But the vast Coed y Brenin forest dominating the

view west put a damper on my enjoyment and, sadly, blocks of forest

were the predominating feature all round. Our mountain tops are

becoming oases in a desert of forestry which goes to feed the chip

board factories and pulp mills. My heart sinks when I realise that the

development of new and hardier species of conifer will enable trees

to be planted to a greater height. Perhaps soon even our mountain

tops will be enveloped, and North Wales will become a boring

switchback of green carpet like much of Scandinavia. However, the

south west ridge of Rhobell Fawr is still clear of trees and provides

a gentle descent. I followed a magnificently constructed dry-stone

wall until, at Bwlch Goriwared, I met a good track coming over from

the west. The end of a walk is important when assessing its overall

quality. A long bash over miles of metalled road leaves you with

bruised feet and a short temper.

Not so today, for the descent from

Rhobell Fawr continued in an idyllic manner as the path led through

lush pastures, the air heady with the scent of gorse, may and

foxgloves. Hazel and alder grew in the hedges and a pair of buzzards

soared overhead. With the sun now high in the sky the sheep were

panting, even in the shade of the walls, and the hills were

shimmering. My usual haunts are the fells of the north of England and

the Scottish Highlands and I delighted in the typically Welsh

scenery. With small fields, woods, rock buttresses, lichen encrusted

boulders, tiny whitewashed cottages with slate roofs, a proliferation

of bracken and ferns and butterflies, where else could I be but

Wales? We become so used to expressing outrage at erosion and litter

and man's despoliation of the countryside that it is rare to have to

cope with other emotions stimulated by perfection. This was such an

occasion and it left me feeling quite dizzy. A short cut along a

marked Public Footpath (Llwybr Cyhoeddus) took me past the farm of

Cae and then I emerged above the tiny village of Llanfachreth with

its steepled church and line of terraced cottages. I stopped at the

tiny shop to buy a can of coke. The local inhabitants were conversing

in Welsh but broke off at my arrival and greeted me in English.

This

circular walk hugs the steep slopes of Foel Cynwch and returns along

the shore of Lyn Cynwch. I took the lakeside section of the walk

enjoying the shade provided by overhanging sycamores and oaks. The

blue rippling waters of Lyn Cynwch set against the backcloth of Cader

Idris maintained my mood of elevation until, at 1.00 p.m., I crossed

the bridge over the Afon Wnion and entered the fine old town of

Dolgellau. Dolgellau, county town of Merioneth and centre of the

great Gold Rush in 1862, but today choked with coaches and day

trippers and the streets littered with ice-cream wrappers. I was back

to reality. ■

Richard Gilbert 1983: First published in Climber -June 1983