Len

and I thought we knew everything that the Buachaille Etive Mòr can

produce, but our old friend of innumerable ascents had a surprise in

store for us on a bleak cloudy day when the air was full of damp as we

donned our boots.We had been trying to arrange this climb for

quite a while. Len had been out of action due to leg trouble and it was

two years since we had been linked by the rope.

He had been telling me how much he had been missing rock climbing and the zest for living you feel at the end of a hard day.Right

now our arrangement did not look quite so attractive as we slung our

sacks and set off up the north-east face as we have done on many other

ascents.

Len wrote the two-volume SMC Climbers’ Guide to Glencoe, so has a unique knowledge of these crags.As

yet we hadn’t discussed what we might climb. We simply kept going until

we found steepening chutes of grey-pink stones becoming rock and struck

up until we found ourselves in Crowberry Gully.

A sharp exit on

its left wall and we were soon at the foot of its retaining ridge which

is one of the great classics of Scottish Mountaineering.It was climbed direct for the first time in 1900, four years after its very first ascent by its easiest route.

Normally

we scramble up to Abraham’s Ledge without the rope, but we found the

introductory cleft so awkwardly slippery that we were glad to rope up

for the next 60 ft. pitch where I made full use of the excellent

handgrips.My feet were slipping on holds that felt as if they

had been soaped and I would have been glad of the friction of

old-fashioned tricouni nails.

Len’s rubber soles were doing the same.“I’ve never known these rocks so greasy,” he said. “It must be the result of the summer we didn’t have.”He

surprised me however by not taking the line of least resistance but

setting off on Greig’s Ledge which has a very awkward and exposed move.

I

was not sorry when its slippy surface persuaded him to take the easier

and lower detour of the original route, though even it required

exceptional care, it was so slimy.Back on the airy crest I took

over the lead again hoping for better things on cleaner rock. This

section is steep and pleasant as a rule, but not that day.

At the

end of my rope I came on a young climber belayed on the only ledge

watching his leader trying to make a turning movement round an edge

which would take him out of sight of us.He made it just as Len

joined me, but there seemed to be something holding him up beyond and

all of us on the ledge were getting very cold.

Just as the leader was running out of rope he shouted that he had found a stance.“Come

on!” he called to his second—easier said than done for the youngster

hadn’t a clue how to tackle the problem. After he had swung off on the

rope three times he shouted up that he wasn’t going to make it.

“You’ll have to,” came the not very reassuring answer. “You’ve got to get up.”Len

and I had been quietly discussing an alternative route out to the

right. He set off on it, while I took the worried climber in hand.

“There

are some holds there that you’re not using. Now if you do what I tell

you you’ll get up all right. Don’t hurry your movements. Place your

feet, keep your balance and try to keep moving.”He nodded and then by way of explanation added, “I’ve never climbed before today.”

He

did well, placing his feet as I had suggested, and while he was moving

Len had gone right and was above him ready to give a hand if he needed

it.

But he got over the bulge which was the crucial bit, and in

two more rope-lengths we were all up, passing a third party on the ridge

so that we had the delightful crest of the Crowberry Tower to

ourselves, even if it was only a point in space with no horizon.

Now

we were in great spirits. Even if the ascent had not been “enjoyable ”

because of the grease, the concentration required had worked its magic.

As we went back down by the Curved Ridge we felt we had had a great day.

Tom Weir : First Published in The Scots Magazine 1980

A recent trip with an enthusiastic group of Chinese climbers, reminded me of what the sport was like in the UK before ease of travel changed perceptions about the distant hills. On that occasion we travelled first across the huge city of Kunming by local transport to reach the northern bus station. Then by bus for several hours to reach Fuling County where we hitched a lift on a horse and cart to take us up a dirt road into the Fuling Hills of Yunnan. This for a weekend rock climbing in a deep limestone valley in that range. The journey took so long that there was only time to climb Saturday afternoon and Sunday morning before we had to start back for town. We slept out beneath an overhang and to say my companions were boisterous and good company is true.

No one owned a car; all had to work or study and this small group was made up of the only really active climbers in Yunnan, a province with a population as large as England. In recent climbing commentaries the reasons for the ever upward, spiralling standards of performance have been placed on technical and equipment innovation, and the modern trend for enthusiasts to eschew the bar for the climbing gym in search of greater strength and fitness. No commentator seems to appreciate that ease of access provided by modern transport has also helped to bring these developments about. This allied to the change in general affluence and with more leisure time being available to Joe climber. It is now feasible from the north of England via the budget airlines to have long weekends in Fontainebleau or Chamonix.

When I started to climb in 1947 at the age of eleven none of the activists I knew owned transport, petrol was rationed, and the only way we could travel was by train or bus. My first trip to the Peak District in 1948 from Leeds was like an expedition. We arrived by train in Sheffield and although we had heard of Stanage, we did not know where it was. We wandered around the city centre asking if anyone knew how to get there. Eventually a kindly soul (we must have struck it lucky for there is not many of them to be found in south Yorkshire) advised us to catch a bus out to a terminus above the Rivelin valley, and we walked from there. I guess that was a feature of the age, if you were not prepared to walk you did not get to climb. Until 1950 we were mostly confined to West Yorkshire outcrops, but at Whitsuntide that year petrol rationing finished and my companions and I discovered, hitch-hiking!

To the uninitiated this is a relatively simple activity, you stick out your thumb and if you're lucky a vehicle will pick you up. But nothing could be further from the truth! To be a good 'hitcher' requires tactical ability, territorial positioning and cunning to outwit any other would be riders. There were still very few cars on the road, but people were much more willing then to give lifts, and by this method I travelled most weekends to the Lake District, or Wales and for my main holidays visited Scotland. In 1951, aged 15, I hitched on my own to Glen Brittle, a journey which took three days and nights. You could reach parts of the Himalaya now in that time span. However hitch-hiking often proved to be slow and tedious, and soon rising affluence meant that nearly any climber who could raise the deposit, bought a motor-bike on the never-never (HP). For a while the adventures that this mode of transport inevitably provided many narrow escapes, and multiple crashes became centre stage in the climbing-raconteurs repertoire. This was the golden age of the British motor cycle industry with models like AJS, Norton, Ariel, Royal Enfield, BSA and Triumph dominating the market. And like my contemporaries I survived several crashes, including a five-bike pile up in Ennerdale.

Climbers and motorbikes proved to be a lethal combination and by the mid-fifties most had moved on to vans. These proved to be ideal for a weekend climbing, you could sleep in them, carry masses of gear and bodies and some had a surprising turn of speed. My first trip abroad was in 1955. Travelling by train via France I visited the Inn Valley, the Wilde Kaiser and the Dolomites. Such a journey was then a major undertaking, for the French Chemin de Fer was not then the TGV of today. The steam engine broke down at Chalons, and we had to wait 24 hours before a replacement could be found. In 1958 I went to Chamonix (with Joe Brown, his wife Valerie and Joe Smith) again by train. It took so long to get there that today you can reach Tibet in less time.

I bought my first motor car for thirty pounds off a school friend in 1955. A pre-war Y type Ford, and the following year I replaced it with an Austin A40 van. After the 1958 trip most of my continental journeys were by using private transport, but even then sometimes the delays were considerable. The worst being when the right wheel front suspension of my van literally collapsed, and I just made it to a garage north of Paris, limping through its front door, at which the wheel gave up the ghost and fell off! Much to the amusement of the French mechanics working there, who then took three days and hundreds of pounds to get me back out on the road again.

In 1961 I made my first visit to the Greater Ranges (shades of Rum Doodle?) and we travelled to Bombay by a first class passenger liner from Liverpool. A journey which took a month, and which was a revelation to such as myself, a working class lad from Leeds 6. We had to dress for dinner and on the return journey we even made it onto the Captain's table! By the time we reached India I had almost forgotten the purpose of our journey, and I have to confess I could have made a profession out of being a gigolo on such a liner. My second such journey to the Himalaya in 1964 was to be an epic of endurance, driving out from Leeds to Kathmandu, which took six weeks to complete. We needed to drive because of financial stringency. After many days in the mountains, I had to come home alone across Nepal and India to Bombay with our equipment, in heavy shipping crates (in that era you had to take out what you brought in or pay massive customs dues) and from there I sailed back to Liverpool.

The whole trip lasted for me from June 1964 until January of 1965. To greet me at the end of this marathon on the pier at Liverpool was one of our expedition members, Don Whillans. Who greeted me thus, 'Don't think have come to meet thee. Have just come to get me bloody gear!' At least you always knew where you stood with the Villain. In 1966 I made an equally long trip to South and North America. Sailing on a cargo boat from Liverpool to Peru, with the expedition equipment, on which I was a supernumerary, and for which I was paid one shilling (5p) a day. This again took a month and the only entertainment was to watch the same pornographic film every night which was shown in the galley. It was called 'The Witches Brew' and the crew knew what little dialogue there was just as well as the 'porn stars'.

After climbing in the Cordillera Blanca, and visiting Cuzco, Machu Picchu I set forth on my own to journey to Yosemite. I travelled via Ecuador, then on to Mexico City and from there, as my funds had dissipated, I had to hitch hike. It took me ten days to get to The Valley, a journey I will never forget, for once into the USA so many 'characters' picked me up that they are still etched on my consciousness almost forty years on. Such as a member of the John Birch Society who was armed ready to defend himself in case of race riots, and a gentle muscle Mary, a giant body builder from Los Angeles's Venice beach, an early member of the then fledgling Gay Liberation Front!

I guess the 'sixties were probably the last decade when necessity forced climbers to undertake such lengthy journeys time-wise, but I do not envy modern day expedition members, for they often miss out on a possible wider experience by simply concentrating solely on their climbing objectives. Air travel is now so comparatively cheap and available, that in the time it took for us to drive to Kathmandu in 1964, they have been and come back. My last big journey in that decade was via another expedition to the Indian Himalaya in 1968, after which I set out on my own to travel the subcontinent north to south. I left Delhi in August and ten weeks later fetched up in Sri Lanka.

Travelling by bus and train I had of course adventures and I think damaged my digestive system irrevocably. In Madras having eaten curry every night for weeks, I decided on the ultimate—a Madrasi. The Indian curries you eat in the UK are nothing like the real thing, and so I wandered into a famous such restaurant in that city. When I ordered the waiter looked at me as if I was mad, 'Oh very very hot, Sahib!' he advised. Nonchalantly I passed this off with a `Jaldi!' and so the steaming concoction eventually arrived. It proved to be the atomic bomb of curries, but I could not lose face as the whole of the staff gathered to watch me eat it.

Somehow I managed to get most of it down but I have never really liked hot curries ever since. Like many other climbers before me, lack of funds forced me to undertake what were in retrospect very educational journeys. They opened my eyes to other cultures, other languages and to some of the problems facing us all as the citizens of a fast shrinking world, dogged by over population, poverty, disease, famines and a universal lack of access to education and health services, allied to long term environmental destruction and degradation.

Such journeys were also an adventure. And before anyone declares doubt about such a statement I can assure them that when I was hitching, on my own late one night at Fresno, California a huge gorilla of a guy ambled over out of the darkness and aggressively demanded I give him some 'chocolate', I was more frightened than I have ever been whilst actually climbing!

Dennis Gray 2006: First Published in Loose Scree July 06

My first brush with Little Brown Jug was the worst. It happened on December 26th., 1962, the first day of the great freeze-up in that terrible winter that helped kill Sylvia Plath. In an excess of Christmas enthusiasm, Peter Biven and I decided to attempt the second ascent of Peter's high-level girdle of Bosigran, Diamond Tiara. In those days. Diamond Tiara seemed particularly well named; it was considered to be one of the hardest climbs on the cliff, and it was certainly the longest -nine hundred feet of Hard Very Severe. We took three days to complete it, but, for me, the first day was the nastiest since it entailed reversing part of the top slab of Little Brown Jug.

A blizzard was blowing across the top of the crag - so hard, mercifully, that none of the snow was sticking to the face. Even so, teetering with frozen fingers down the small, widely-spaced holds, with nothing but air between the lip of the slab and the wild sea below, was not quite what I had had in mind as a cure for turkey, Christmas pud and booze.

Since then, I have climbed LBJ four times - with Peter again, with Mike Thompson, and twice with my then teenage son, Luke - and the slab has always given me a bad moment before I started up it, although each time it has seemed easier, despite the fact that, at my last ascent, I was unfit, overweight and fifty-five. Knowing the route helps, of course, but pleasure helps even more. The top pitch of LBJ is one of the finest on Bosigran and, for me, Bosigran is the best of all possible places to climb. The granite is steep and faultless, the approach is short and horizontal, and the views are sensational: waves thundering in around Porthmoina Island, seabirds wheeling and crying, and, off to the west, headland succeeding headland, with Pendeen lighthouse sticking up like a white thumb against the horizon of the Atlantic.

Although I know, rationally, that I must have climbed on Bosigran on dull days or in the rain, all my recollections of the place, apart from that winter blizzard years ago, are of warm rock, blue sea and sunshine. LBJ combines all of Bosigran's best qualities: it is delicate, technical and strenuous by turns, and the rock is always steep and faultless. It begins at a smooth, pale wall that, at first glance, appears to be almost blank. But the line of little nicks that cross the wall diagonally to the left feel positive, even comfortable, to the fingers, and the angle is not as fierce as it looks from below. The upward traverse ends at a shallow, blackish corner below a vertical crack. The top of the crack overhangs slightly and is often damp, but it leads to a large ledge with a piton belay at its left end.

This belay is shared with three other climbs - Doorpost, Bow Wall and

Thin Wall Special - so, on a sunny holiday weekend, it can be as busy as Victoria Station at rush hour. The second pitch is the mixture as before: an ascending diagonal traverse - to the right this time - across a slabby wall that is sometimes wet. It is shorter than the first traverse, a little harder to start, but far easier to finish. It leads to a jumble of large blocks which are crossed by Doorway and Ledge climbs - another rush-hour tangle of ropes, but at least you have the belay to yourself.

The rock above overhangs and is as strenuous as it looks, as well as technical -hard for a short man to start, hard for a tall man to finish. A difficult layback up the blunt edge of the overhang brings your face level with a sloping shelf beneath an impending wall. At the back of the shelf, low down, is the little brown jug itself - a slot, like a miniature letter-box, to sink your fingertips in. The problem is to step up delicately onto the shelf while preventing the wall above from pushing you out of balance. In the wall at the upper end of the shelf, there is a piton for protection. Off to the left, and level with piton, a little lump of rock protrudes from the base of the slab above.

The lump is oddly shaped - like a stone gargoyle on a cathedral, with all its features smoothed away by the weather - and the move you have to make to reach it with your left foot is also odd - at once balancy, strenuous and committing. There are only little nicks on the slab above to help pull yourself across, while your right foot bridges out onto nothing in particular. Another nick, another pull, and you are standing on the stone head at the bottom of a steep slab. You move up the slab delicately, cautiously, on very small finger flakes. Halfway up, the footholds run out, but there is a vertical slot for the right hand which brings you to within a move or two of a large ledge and a belay.

Above the ledge is another overhang, big and brutal and split by a rough crack. It is intimidating to start and far too steep to allow you to pause and insert pro-tection. But the edge of the crack is perfect for laybacking - up to the overhang, around it, and on up - laybacking all the way until you are standing upright in the sunshine among the mossy boulders on the top of the cliff. For myself, I can guarantee the sunshine. Ever since that first Christmas descent of the pitch, I would never again go near the route in bad weather.

Al Alvarez

Dropping down from the craggy heights of Dyniewyd into the pastoral valley of Nantmor.

The car park near Gelli Iago was surprisingly full for the middle of the week. I had never considered this quiet land of modest whale backed hills and ewe sprinkled moors to be anything other than the haunt of the occasional iconoclastic rambler. After all, the nearby mountains of Yr Wyddfa, Moel Hebog and Moel Siabod would, I might have thought, offered themselves as more tempting targets for the typical Welsh peak bagger. I suppose the Gelli Iago track up Cnicht is a common approach to this popular wee peak so I reassured myself that most of the cars almost certainly belonged to walkers who at that very moment, were trudging up the rutted tracks and shifting scree which zig zagged up to Cnicht's crenellated ridge.

Nantmor ribbons through the quilted tapestry of Snowdonia like a gilded thread. A slumbering hint of wilderness which generally retains its character and tranquillity by virtue of its modest range of vertically challenged hills. Moel Meirch..Yr Arddu..Moel Dyniewyd and Mynydd Llyndy; minor stations of the cross when compared to the brooding massif to the north. Liam a son of fifteen years and a remarkably tolerant, accommodating and good humoured soul that you could wish to meet- considering the places I had dragged him up to!-accompanied me to this quiet backwater. Both encouraged by a rare window of good weather which had opened up within the generally dreary summer we had experienced so far. Leaving the old quarry we sheep tracked through the cropped pastures twixt Mynydd Llyndy and the shattered grey spoil heaps. Our destination hidden within the folding hummocks of bog cotton grasslands and the rusted outcrops where Nantmor's invasive rhododendrons wore their brightest colours.

The robust seed of these distant interlopers carried on the hard winds which came in from the Irish sea beyond the tapering mane of the Moelwynions and rooted within the poor earth in a display of tenacious colonisation. The land hereabouts is studded with old sheepfolds and the occasional crumbling hafod...a summer agrarian dwelling....which meld into the land like stone nests.Roofless and lifeless save the odd crow who preaches from the stone lintels and the world weary ewe who crawls in to die. One hafod we passed nestled impressively within the maw of a beetling cliff—both human and natural facades wrapped in the deep viridian cloak of rampant ivy. Tiny lizards exploded like rip-raps on the warm rocks as our passing shadows startled them into life. Striking west towards the sea, we fell under Llyndy's lower cliff..Craig Mwyner Crag of the miner..and continued up the purple slopes to reach the impressive upper cliff, now re-named Dyniewyd East by the Climbers' Club guide book team.

Dyniewyd East: Paul Work's Llyndy Arete takes the obvious rib on the right

The cliffs hereabouts were not known to me as a traditional climbing venue although I was aware that new router extrordinaire, Pat Littlejohn, who lived locally, had put up some new routes in the past five years. A new routes report in High had suggested that another team had put up the first new lines in nearly 50 years on Christmas Buttress. I vaguely recalled that an old Climbers' Club guide to South Snowdonia had mentioned something about Mynydd Llyndy but regardless of ancient and recent history, I was sure that Liam and I would get something new chalked up before the day was out. A bright sun set in and the clearest blue sky was not enough to overcome the westerly wind blowing in off the sea which cooled us to a degree where each was glad to have brought some warm togs. Pulling on an old baggy top and blowing on cold hands I weighed up the most obvious line, a short clean cracked arete which bookmarked the right edge of the cliff. It looked as if it must have been climbed before and turned out to be a little gem. I wrote this up as Spare Rib and felt it worthy of Mild VS before discovering that it was in fact a 1947 Paul Work route, Llyndy Arete which area guidebook compiler Dave Ferguson had graded at a more modest Severe.

Paul Work was a minor figure in the Welsh climbing scene in the years around the second world war. A Merseysider who had the unique honour of being proposed and seconded for membership of The Climbers' Club by none other than Menlove Edwards and Colin Kirkus, fellow Merseysiders who dominated the pre-war climbing scene in North Wales. Paul Work lived with his wife Ruth Janette Ruck on an 83 acre smallholding in the shadow of Moel Dyniewyd. The harsh realities of wringing a life out of the poor earth of Dyniewyd's western fringes were recorded by Janette and published to popular acclaim in the 1960's. Place of Stones and Hill Farm Story chronicle lives of struggle yes, but also detail the ample rewards of living far from the urban sprawl.

Time consuming as running a smallholding was, Ruth and Paul still found time to leave their agrarian responsibilities behind occasionally and climb amongst the red rocks of their enchanted valley. Paul Work's most popular climb - a relative term considering Nantmor's status as a climbing backwater - remains Christmas Climb, an excellent severe on Craig Dyniewyd, less than half a mile from their home at Carneddi.

With Liam, I had the pleasure of putting up a direct VS version 12 months previously. This came fifty years after Paul Work had established the original. Culturally and philosophically, I felt a great empathy with Paul Work.The chronological dovetailing of our two routes gave me great satisfaction. Christmas Climb and Llyndy Arete were both put up in 1947, a time of ration books, bomb sites and the developing cold war. Political and social upheavals come and go but the stone remains. The climbers' words written indelibly upon a cold page. Apart from exploring Nantmor's lonely outcrops, Paul Work developed a serious - some would say perverse - interest in the equally unfashionable cliffs of Moel Hebog and Aberglaslyn Pass where he established the majority of his routes.

The empathy I felt with Paul Work extended beyond his enthusiasm for lonely, eternally neglected cliffs and outcrops to his rejection of the market orientated rat race where most of his contemporaries remained after the war. His rejection of the dominant social mores and lifestyle choices of that bleak era chimes with anyone who has ever been seduced by the lure of what we describe today as the alternative society. He may have been a minor figure in the climbing firmament but nevertheless, his life was an inspiration to anyone who values creativity and a quiet contented mind over material acquisitiveness and climbing the career ladder.

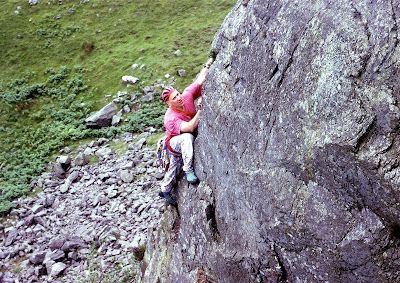

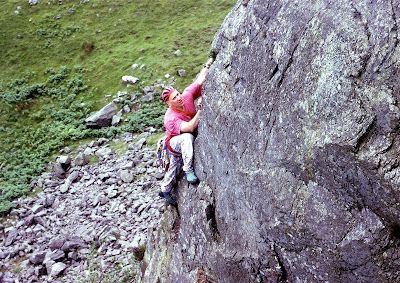

Liam Appleby leads Orbita watched by Henry Hobson

After completing the arete we tackled the capped left slab which gave another entertaining climb through the overhangs at 4c. An unusually clean edge which should have held a clump of vegetation alerted me to the fact that someone else had passed this way before? Later it transpired that guidebook contributor, Dave Ferguson had climbed this line although our lines had deviated above the overhangs. Finally we really did nail a new route. Tao of Stone was another VS which climbed a slab and shattered groove before finishing up a fine, airy arete. Two more new routes on the lower cliff were dispatched before we set off for home. Vasco VS and Orbita VD, were named after two ships my late father had served on. Both within site of Bryn Castell - Menlove's knoll -where I had scattered the old man's ashes and those of his trusty hound Gypsy, seven months previously.

The following week, Harold Drasdo was dragged along. My enthusiasm overcoming his well founded reservations based on previous experiences of my 'fantastic discoveries'! After completing Llyndy Arete I tried another couple of unclimbed lines but not without almost killing Harold when a ledge I was standing on suddenly departed from the cliff and just missed him by an arm's length! Giving up on the upper cliff we picked our way back down to the lower cliff to try out an obvious line which I noticed on the way up. This perfect, sharp edged arete was striking in its purity. It stood proud of the main body of the cliff like a serrated knife. Taking care with some more loose rock within the V groove at the base I bridged up and pulled out onto the arete. Easier climbing led to a half way ledge above which the arete narrowed to a razor's edge before gaining some girth near the top.

Unavoidable loose blocks prevented a direct ascent this time so I tackled a shallow groove on the left. Although short it was quite thin in places and demanded a long, committing reach to settle upon what appeared to be a good jug. When tired fingers finally grasped the thank-God hold it turned out to be a Jesus Christ! hold instead. That is...it rattled alarmingly and threatened to cut short my pioneering activities in the blink of an eye. Affixed to the rock by faith and friction I managed to fiddle in a trusty moac and, breathing more easily, managed to swing up to reach better holds above. This line turned out to be Stonecrop El 5a.

It was clear that the line needed to be completed as first conceived. One week later I returned with Liam and his young friend Henry Hobson to straighten out Stonecrop. The fine line between life and death occasionally emerges from its cliché ridden lair to confront us with the chilling reality of its meaning. June 7th was just another summers day like any other—it could have been Liam's last on earth. I had decided to abseil down the arete to prise off the loose blocks which barred passage to the knife edge arete. Abseiling down a sharp arete is a tricky business. One slip and you find yourself hurtling into the confines of one of the retaining gullies. After struggling to find a sound anchor point I eventually set off and crept down towards the halfway ledge and began to prise loose the most prominent of the rotten flakes which stood like a fang at the base of the arete.

This fang, or perhaps tombstone, would have been more appropriate, rattled alarmingly in its socket. Some cursory pushing and pulling suggested that a good sharp shove should remove it from its root and send it spinning down towards the gully's scree fan 50' below. With Henry stationed across the gully taking photos, I instructed Liam at the base of the arete to take in the slack which trailed beneath me and tuck himself in around the corner at the foot of the arete. I gently rocked the flake back and forth until its unstoppable momentum gathered pace. Increasing the rocking action the fang finally was torn from its socket and, totally unexpectedly, took off on a gravity defying trajectory which was a full ninety degrees out of my calculations. Instead of exploding harmlessly in the gully below, the flake twisted and exploded into space, hurtling down the arete with the accuracy and intensity of a heat seeking missile. At the last nanosecond it glanced off the rock and exploded 'n a thousand sharp fragments through the branches of the holly tree at the base of the arete.

Stonecrop Direct

Liam felt the screaming rush of air as the rock practically parted his hair. Despite being a fraction from certain death, Liam just brushed himself down and calmly stated ..that was a bit close! From my vantage point high above my heart pounded like a drum as the sulphurous smell of exploded rock drifted across the void between us. As calm descended I carried on and finished the line which turned out to be a fine little route...Stonecrop Direct VS-4b. The rest of the afternoon wound down as a series of repeat climbs and gentle rambling twixt crags. After repeating Paul Work's original Christmas Climb we followed the sheep tracks and streams to the old footpath which meanders through the oak woods beyond Carneddi, each lost in our own thoughts but gathered in the solidarity of our labours. Despite the scare I still love Nantmor as much as I ever did. Its texture woven from ancient skeins..its huge music filling an empty sky.

Through tumbled walls

Is accompanied

By lost jawbones of men

And lost fingernails of women

In the chapel of cloud

And the walled, horizon-woven choir

Of old cares

Darkening back to heather

The huge music of sightlines

Every step of the slopes

The messiah of opened rock

Ted Hughes: Remains of Elmet- Faber & Faber

John Appleby: First published in Loose Scree. November 2005.