Footmarks of a cantering man. The perfect title for the rushed memoirs of a recently-fallen politician? Or the souped-up story of some philandering celebrity? No, but the phrase is not new. It is the caption to a drawing, one of a hundred or so illustrating the first comprehensive textbook on climbing, the Badminton Library's Mountaineering, published in 1892. Cantering in this context means descending steep ground by a series of two-footed leaps;

"... the feet falling almost side by side and one immediately after the other... the interval between each pair of steps may be eight to twelve feet."

It is eccentric advice, part of three pages on how to walk downhill, which follow six pages on how to walk uphill ("A certain slight degree of roll, or, to put it more scientifically, of swinging of the pelvis or hips, is of the first importance"). And it is characteristic of an eccentric book, in which most of the text is of a remarkably long-winded, humourless pomposity. The tone is set by the dedication, written by the series editor, the Duke of Beaufort, presumably during pauses in licking the boots (or some other part) of the dedicatee:

"... to HRH The Prince of Wales, one of the best and keenest sportsmen of our time. I can say, from personal observation, that there is no man who can extricate himself from a bustling and pushing crowd of horsemen, when a fox breaks covert, more dexterously and quickly than His Royal Highness... often have I seen HRH knocking over driven grouse and partridges and high-rocketing pheasants in first-rate workmanlike style. He is held to be a good yachtsman... His encouragement of racing is well known... fond of all manly sports. I consider it a great privilege to be allowed to dedicate these volumes to so eminent a sportsman as HRH the Prince of Wales, and I do so with sincere feelings of respect and esteem and loyal devotion.”

If that didn't gain an extra gong for the ducal chest, what would?

After that, it is unsurprising but still rather depressing that every piece of advice to the would-be climber is based on extreme conservatism, utmost caution and a reverence for age and experience. Innovation, in equipment or in the quest for new routes, is severely frowned upon:

If that didn't gain an extra gong for the ducal chest, what would?

After that, it is unsurprising but still rather depressing that every piece of advice to the would-be climber is based on extreme conservatism, utmost caution and a reverence for age and experience. Innovation, in equipment or in the quest for new routes, is severely frowned upon:

"Crampons, or climbing irons, do not find much favour with English mountaineers, and have been spoken of contemptuously on many occasions..........Far too many of these 'variation' routes have been introduced of late years. The art of mountaineering will be better developed and maintained by following as well as possible the old routes, than by attempting at any cost to fashion out new ones... The pleasure of novelty and the flatteries of fame betrayed some of those whose misfortune it was to come late into the field, to attempt an undue multiplication of routes... A limit must, of course, be set to this kind of overproduction, and the good sense of the large body of climbers may be trusted to enforce it."

That forecast was surely as remarkable as the writer's ignorance of human nature. The authors, peering down from their heavenly hut, must be horrified by the climbing scene of today, particularly in Britain:

That forecast was surely as remarkable as the writer's ignorance of human nature. The authors, peering down from their heavenly hut, must be horrified by the climbing scene of today, particularly in Britain:

"... there are many little rocky teeth in the Lake districts of our own country where the mountaineer may find abundant opportunities... These small scrambles are but delightful episodes in a day's walk". But those delightful episodes are not really to be encouraged. They might lead to "... the danger of 'fancy climbs'. Near Snowdon, in the Lake District, and to some extent even in Skye, those who would do some fresh thing have been driven to climb places of extreme difficulty... The novice must on no account attempt them... these fancy bits of footwork are not mountaineering proper..."

Mountaineering proper then meant alpinism, and to have the time and money to climb in the Alps in those days, you were necessarily of the upper crust. So maintaining the dignity of a "Herr" was important:

Mountaineering proper then meant alpinism, and to have the time and money to climb in the Alps in those days, you were necessarily of the upper crust. So maintaining the dignity of a "Herr" was important:

"A flannel shirt without a collar will look untidy, even though worn by a bishop, but if provided with a collar of fine-wove linen, the wearer can always look respectable... no man has a right to go about looking like an ostler unless he happens to be one." And for the ladies, "Three yards round the hem will be found a good width for a skirt, which can be of ordinary walking length... which, in the valleys or towns, does not look conspicuous."

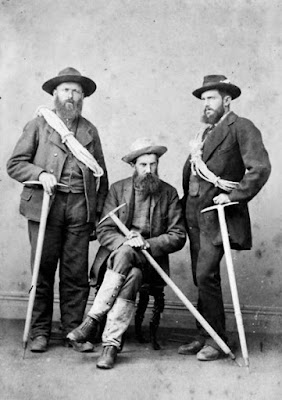

Then there were the guides, those fortunate farmers and hunters whose local knowledge and common sense had acquired considerable value in the eyes of the visiting English gentry. Their assistance had been deemed essential from the birth of mountaineering but recently a foolhardy few climbers had ventured, in the face of senior disapproval, to do without them "Guideless climbing is to be strongly deprecated as a general practice. Under certain conditions it is reasonable enough."

And those conditions? A chapter of 17 pages is needed to describe them but:

"To sum up the question in a few words: every guideless party must consist of three or more members who know each other's climbing well; each must have had a long experience of lower hills in all kinds of weather; must have climbed in the high Alps for at least four seasons with good guides; must have the moral courage to turn back if advisable; must be able to take his share of the work, and lead the party in case of need."

That repetition of the authoritarian "must" jars in a big way now, in these less reverential days. It probably did then, but the Alpine Club bigwigs (five of the seven contributors were past or future presidents of the club) who put the book together seem less interested in encouraging would-be climbers than in warning them off. Keeping beginners in their place - not only behind a guide, but crouched at the feet of their elders and betters - is a recurrent theme: "Untrained men, youths fresh from school, even ladies[!] now climb, or are hauled up, the Alps... Novices must learn that, apart altogether from physical gifts, serious training and considerable experience are absolutely necessary... "

How were all these stern warnings received? By one climber at least, they were taken badly. At all stages of climbing history there have been prominent rebels who, by their actions and their words, have set new standards and encouraged fresh thought. Such a one was A F (Fred) Mummery, revered now as an inspirational climber and author but by no means universally admired then. Indeed, his first application to join the Alpine Club had been blackballed, partly, it is thought, through jealousy of his achievements but mainly because, as part-owner of a tannery and therefore engaged in trade, he was not, in the eyes of the old and crusted, a gentleman. Fortunately for the reputation of the club, wiser thoughts eventually prevailed and he was welcomed at the second attempt. In 1895, Mummery published his wonderful reminiscences, My Climbs in the Alps and Caucasus, perhaps the most enjoyable book ever written about climbing. The pleasure comes not so much from the descriptions of exciting first ascents, stimulating though they are; it arises from the unforced flow of the prose and the cheerful modesty and good humour which adorn every page:

Then there were the guides, those fortunate farmers and hunters whose local knowledge and common sense had acquired considerable value in the eyes of the visiting English gentry. Their assistance had been deemed essential from the birth of mountaineering but recently a foolhardy few climbers had ventured, in the face of senior disapproval, to do without them "Guideless climbing is to be strongly deprecated as a general practice. Under certain conditions it is reasonable enough."

And those conditions? A chapter of 17 pages is needed to describe them but:

"To sum up the question in a few words: every guideless party must consist of three or more members who know each other's climbing well; each must have had a long experience of lower hills in all kinds of weather; must have climbed in the high Alps for at least four seasons with good guides; must have the moral courage to turn back if advisable; must be able to take his share of the work, and lead the party in case of need."

That repetition of the authoritarian "must" jars in a big way now, in these less reverential days. It probably did then, but the Alpine Club bigwigs (five of the seven contributors were past or future presidents of the club) who put the book together seem less interested in encouraging would-be climbers than in warning them off. Keeping beginners in their place - not only behind a guide, but crouched at the feet of their elders and betters - is a recurrent theme: "Untrained men, youths fresh from school, even ladies[!] now climb, or are hauled up, the Alps... Novices must learn that, apart altogether from physical gifts, serious training and considerable experience are absolutely necessary... "

How were all these stern warnings received? By one climber at least, they were taken badly. At all stages of climbing history there have been prominent rebels who, by their actions and their words, have set new standards and encouraged fresh thought. Such a one was A F (Fred) Mummery, revered now as an inspirational climber and author but by no means universally admired then. Indeed, his first application to join the Alpine Club had been blackballed, partly, it is thought, through jealousy of his achievements but mainly because, as part-owner of a tannery and therefore engaged in trade, he was not, in the eyes of the old and crusted, a gentleman. Fortunately for the reputation of the club, wiser thoughts eventually prevailed and he was welcomed at the second attempt. In 1895, Mummery published his wonderful reminiscences, My Climbs in the Alps and Caucasus, perhaps the most enjoyable book ever written about climbing. The pleasure comes not so much from the descriptions of exciting first ascents, stimulating though they are; it arises from the unforced flow of the prose and the cheerful modesty and good humour which adorn every page:

"When the rope came down for me, I made a brilliant attempt to ascend unaided. Success attended my first efforts, then came a moment of metaphorical suspense, promptly followed by the real thing.....They said they were waiting for me, but the abandon of their attitudes suggested that this was not the whole truth. Seeing some signs of movement, I suggested lunch..."

Above all there is the explicit and unqualified declaration that climbing is fun (a truth, incidentally, which even today evades some writers, judging by the war-like metaphors and pseudo-mysticism - confronting demons and the like - occasionally described to a good day in the hills). Amongst the tales of derring-do are sandwiched polite but explicit refutations of the general spirit and much specific advice contained in Mountaineering. Take the question of guides. Mummery had used them frequently - indeed, Burgener and Venetz and others had led him up several of "his" notable first ascents - so their use could hardly be condemned. But times had changed. Whereas guides had once been friends and advisers, sharing the spirit of adventure and uncertainty which spurred an expedition, most of the originals had retired or died, and their successors - far more numerous and with many more clients - were more akin to contractors who could "lie in bed and picture every step of the way up" and determine to the minute when their charges would reach the summit and when they would return to their hotel.

That, in Mummery's view, was not adventure, and neither was the repetition of existing routes when there were myriads of potential new lines waiting exploration."The true mountaineer is a wanderer... a man who loves to be where no human being has been before, who delights in gripping rocks that have never felt the touch of human fingers, or in hewing his way up ice-filled gullies whose grim shadows have been sacred to the mists and avalanches since earth rose out of chaos."

We - most of us, anyway - might find that description a touch difficult to live up to, now that new lines which are both climbable and accessible are rather hard to find. But few, if any, would disagree with Mummery's further point - at odds with the establishment of his day - to the effect that overcoming challenges using one's skill and strength was absolutely integral to the pleasure of the sport. It didn't mean that those who sought difficulty were oblivious to the glories of the mountains: "

... I should still climb, even though there were no scenery to look at, even if the only climbing attainable were the dark and gruesome pot-holes of the Yorkshire dales. On the other hand, I should still wander among the upper snows, lured by the silent mists and the red blaze of the setting sun... even though in after aeons the sprouting of wings and other angelic appendages may have sunk all thought of climbing and cragsmanship in the whelming past."

Nowadays we would probably substitute indoor walls for potholes, but the case for climbing as a multi-faceted sport is well made. The BMC couldn't put it better. As we know, Mummery didn't live to learn the success of My Climbs as, later in its year of publication, he was killed, with two Gurkha companions, during the first attempt on Nanga Parbat - the first attempt, indeed, on any Himalayan giant. The wings and other angelic appendages arrived too soon.

This tale of two books nevertheless has a happy ending. The chief author of Mountaineering was C T Dent, a past president of the Alpine Club who, having made the first ascent of the Aiguille du Dru, could be said to have practised the opposite of what he preached in his book. If he was offended by Mummery's criticisms he had the perfect opportunity to respond in kind, when reviewing My Climbs in the 1895 Alpine Journal - a review which, it is clear from the use of the present tense, was written before Mummery's death, so making sympathy or pulled punches unnecessary. How did Dent react? Not with rancour, but with generosity. His review is wholly favourable. It wasn't possible to ignore his differences with Mummery, but: "It is true that Mr Mummery does not always express approval of the maxims enforced in [Mountaineering]. And he certainly does not always practise the principles laid down. But Mr Mummery is an exceptional man, and they who are qualified by experience to make rules are privileged to break them.... It is far from our intent to make the profound mistake of answering criticism [as] it is not necessary... Mr Mummery is an ally, not an opponent."

Nowadays we would probably substitute indoor walls for potholes, but the case for climbing as a multi-faceted sport is well made. The BMC couldn't put it better. As we know, Mummery didn't live to learn the success of My Climbs as, later in its year of publication, he was killed, with two Gurkha companions, during the first attempt on Nanga Parbat - the first attempt, indeed, on any Himalayan giant. The wings and other angelic appendages arrived too soon.

This tale of two books nevertheless has a happy ending. The chief author of Mountaineering was C T Dent, a past president of the Alpine Club who, having made the first ascent of the Aiguille du Dru, could be said to have practised the opposite of what he preached in his book. If he was offended by Mummery's criticisms he had the perfect opportunity to respond in kind, when reviewing My Climbs in the 1895 Alpine Journal - a review which, it is clear from the use of the present tense, was written before Mummery's death, so making sympathy or pulled punches unnecessary. How did Dent react? Not with rancour, but with generosity. His review is wholly favourable. It wasn't possible to ignore his differences with Mummery, but: "It is true that Mr Mummery does not always express approval of the maxims enforced in [Mountaineering]. And he certainly does not always practise the principles laid down. But Mr Mummery is an exceptional man, and they who are qualified by experience to make rules are privileged to break them.... It is far from our intent to make the profound mistake of answering criticism [as] it is not necessary... Mr Mummery is an ally, not an opponent."

'Near Interlaken'. John Ruskin Watercolour

Which only goes to show that, whatever is visible on the surface, when you delve beneath the skin all climbers are good guys.

Which only goes to show that, whatever is visible on the surface, when you delve beneath the skin all climbers are good guys.

Ben Stroude: 2019