Artist:Ricky Blake

He who experiences the unity of life, sees himself in all beings, and all beings in himself’ The Buddha.

One would expect that climbers would be bound by a strict conservation ethic, but unfortunately that is not always the case, and some of the most pristine of natural sites have suffered severe degradation in recent years. I guess it was easier to be high minded and highly motivated to conservation when our numbers were small, but as our sport becomes ever more populated there is a real task in educating the new comers, mainly coming from an urbanised existence, into the fragile nature of crag and hill environments. Historically they have many role models within the wider realms of mountain activities to emulate, and it is a source of some interest and pride that three of the most influential figures in this respect, John Muir, David Brower and Amory Lovins were all mountaineers. Between them they cover the whole time line from the mid-nineteenth century to date.

John Muir (1838-1914) was born in Dunbar in East Lothian but he was emigrated; to the USA with his deeply religious family when he was eleven years old. After growing up on the family farm in Wisconsin, working around the clock driven by a father who had him memorising from his earliest years huge chunks of the King James bible, he moved to work in Canada. Where he might have remained, but after suffering an industrial accident, he set forth and walked the hundreds of miles, down through America to the Gulf of Mexico. This gave him the taste for the adventure he craved, and from there he found his way to California and the high country of the Sierra’s, and to Yosemite, eventually making the State his permanent home.

For the next decade, from his first visit to Yosemite in 1868, he wandered amongst and climbed to the summits of the Sierra Nevada. Making many first ascents, mostly accomplished climbing solo. His ascent in 1869 of Cathedral Peak (10,940ft’) in Yosemite was impressive, and probably at that date one of the most difficult such climbs in North America. To write that he was physically robust is an understatement, for his equipment was rudimentary and he endured many bivouacs in the mountains living off hard tack, sleeping wrapped in a single blanket. Besides his climbing activities, he was educating himself, heavily reading and studying, and it is obvious that he was highly gifted for he quickly realised that it was glacial and river action that had formed Yosemite, not volcanic activity as promoted by the then leading US geologists. He then undertook some climbing trips further afield, to Glenora Peak now in British Columbia, to Mt Rainier making the seventh ascent of the peak, and to Alaska. The story of the rescue on Glenora Peak of Samuel Hall Young by Muir, written up by the injured man, deserves to be a classic of mountain survival stories. At one stage in the narrative, hanging out over a 1000ft drop to the glacier below, Muir pulled his companion up to a safe perch, dragging him by his teeth biting into his collar!

John Muir's Lost Valley; Hetch Hetchy before and after the state sponsored flooding of the valley.

It was during his time in Yosemite when he worked as a shepherd and at other tasks that he came to realise that human beings are merely a part of the natural world, and not the centre of it. If you look at photographs of Muir from this era, lean, spare and heavily bearded, he looks what he later became, a prophet of the spiritual quality of nature, and from thereon he became an ardent supporter of the wish to preserve such wilderness areas. He petitioned Congress with the need for National Parks to be established and in 1890 a bill was passed that set up the first: Yosemite. His continued activism in this cause then led on to other areas being so designated, including the Sequoia National Park, and he is now universally recognised as the ‘Father’ of those designations.

Over the next years Muir became a National figure in the US, writing many books and essays about his adventures in the Sierras, and his wish to conserve and preserve the natural environment for all his countries citizens. In his campaigns he met with Congress Men, the President and other like minded outdoor enthusiasts. This led on in 1892 to him co-founding The Sierra Club. Which today, via many stages in its development, has become the largest and most influential grassroots environmental organisation in the USA with millions of members, and Chapters across the Nation; The Sierra Club has a permanent base in Yosemite, and Muir’s later family residence in Martinez, California is also now a National historic site.

Few mountaineers can have made such an impact on subsequent generations, for as an outstanding ‘Wilderness Prophet’ who helped to lay the groundwork for modern environmental thinking, he has inspired so many others to carry his message and to act. In the UK the John Muir Trust founded in 1983, is dedicated to protecting and enhancing wild places, and is the owner of some of the most important natural and mountain sites in the UK, including Ben Nevis. There is the John Muir Way, a 215 kms long distance walking route running from Helensburgh in the West to Dunbar in the East. And the Muir original family home in that town is now a museum. The John Muir Trail in the US is recorded as that Country’s premier hiking route, 211 miles in length passing through Yosemite, Kings Canyon and Sequoia National Parks.

His books are all still in print, but what might be a failing in this commentator, is that I find his writing too set in his religiosity, and even child like, but they are honest and true to his mission of enthusing his readers about the restoring spirit to be found in the earth’s wild places (In later life he travelled widely including ascending the Mueller Glacier on Mount Cook in 1903). Anyone who is interested in reading more about Muir’s mountaineering should study, ‘John Muir’s Greatest Climbs’ by Graham White published by Canongate in 1999. Finally the Muir name is now so well used in the US, in educational and ecological nomenclatures on an almost industrial scale, that I will mention only one more, April 21st is John Muir Day, his birthday.

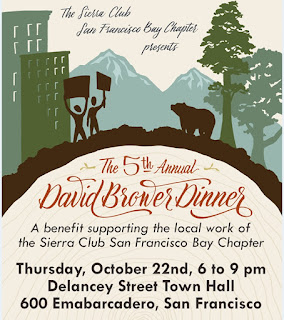

David Brower:Image The Sierra Club

David Brower (1912-2000) was another key figure in the development of the modern environmental movement, who came to this through his interest in mountaineering. He was born in Berkeley, California and it was whilst he was a student at its University he began to climb. He quickly made a name as a high standard friction climber and he was one of the first to attempt an ascent of the Lost Arrow Spire in Yosemite. A fellow student was Hervey Voge, who later wrote one of the earliest climbing guidebooks to the Sierras, and with whom in 1934, Brower traversed the bulk of the High Sierras from Kearsage Pass to Yosemite, summiting 59 peaks in 69 days. Voge had persuaded Brower to join the Sierra Club in 1933, an organisation which in later life became synonymous for many years with the name Dave Brower. But that was in the future, and on graduating he took up a post with The University of California Press, and it was because of the knowledge he gained of the publishing process which enabled him to launch many outstanding wilderness and mountaineering volumes in the years ahead.

In 1935 with a group from the Sierra Club, he attempted to climb Mount Waddington (13,186ft) in British Columbia. He and his friends had by then begun to winter climb in the Palisades, a part of the Sierras and they were as at home on ice as rock, but the weather in the Coastal Range is notoriously bad, and their attempt was beset by bad weather and despite repeated attempts they had to retreat . But in 1939, Brower along with Bestor Robinson, Raffi Bedayn and John Dyer decided to take on the challenge of ‘Shiprock’ in New Mexico. This huge volcanic peak had already defeated 12 previous attempts by groups from around the USA and it was known as ‘the last great American climbing problem’. Initially they tried to climb the mountain by ascending and descending from their high point each day, but they realised that they needed to keep climbing up from a bivouac. After some fine leads by all the other three, belayed by Bedayn, who had made a name for himself as a holder of some big falls, they succeeded in ascending ‘Shiprock’. Not without controversy for they used four bolts on the climb, two for aid, and two for belays. This was the first time bolts were placed on a climb in the USA!

The war then intervened, and Brower was called up as a Lieutenant and inducted into the 10th Mountain Division, an elite unit with whom he served as a mountain, and skiing instructor. He put together for this ‘The Manual of Ski Mountaineering’ which subsequently continued in demand post war in several editions. The 10th Mountain Division was involved in several key battles in North Italy and Brower earned a decoration for bravery in action in the Pre-alps. Returning to California on demob Brower along with Ansel Adams, and attorney Dick Leonard were the young Turks who set to and revitalised the Sierra Club which had become somewhat atrophied during the conflict. One has to understand that in the USA, there was not long standing local climbing clubs at that date, but what there was in California were the local Chapters of The Sierra Club, who organised climbing meets and beginners events at such outcrops as Stoney Point, where climbers like Royal Robbins learnt to climb as a member of the Los Angeles Chapter, and it was through these and building up the membership that a revitalised Sierra Club was reborn.

In 1952 Brower became the first Executive Director of The Sierra Club, and he brought a dynamism to the role not previously experienced in such a body, taking on the big corporations, and opposing developments the organisation felt damaged the natural environment such as a series of planned dams within the Grand Canyon, on the Colorado River, and lobbying against these by taking out whole page advertisements in National newspapers, by appearing in the media, arguing the conservation cause, and winning a series of high exposure battles. In 1960 Brower drawing on his publishing experience launched a series of coffee table, exhibit format style books amongst which was in 1962, ‘In Wilderness is the Preservation of the World’, with photographs by Eliot Porter. Which became an international best seller; I still have my copy, and the pictures are still gob smacking. The Sierra Club also published climbing guidebooks to the Sierra, and Steve Roper and Alan Steck’s, ‘Fifty Classic Climbs in North America’.

Campaigning takes its toll on friendships and tempers, but mainly because of Brower’s expensive campaigns and his opposition to atomic power generation, worried by the problems of security and the expense of decommissioning, he faced serious criticism for his actions. A vote of no confidence was defeated in 1968, but in 1969 the heat was on again and this time he resigned. His old friends, Ansel Adams and Dick Leonard voted against him, but at least he could leave knowing he had put The Sierra Club centre stage with a massive increase in membership and its public profile.

But you cannot keep a campaigner like Brower quiet, he went off and founded in 1969 with Anderson, Aitken and Jerry Mander, a new environmental agency, with an international scope, ‘Friends of the Earth’. This is now bigger than The Sierra Club, with an international network of organisations in 74 countries; its first overseas employee was Amory Bloch Lovins, (more of him anon) and its Headquarters are in Holland. Brower was so famous in the following decade that he was nominated twice for the Nobel Peace Prize, and he was affectionately referred at as the ‘Arch Druid’, reported on as such by a New York Times reporter, John McPhee in a series of essays; ‘Encounters with the Arch Druid’. Two of Brower’s own books were high sellers, ‘The Population Bomb’ this a major alert about the affects of a massive growth in the world’s population, and a truly environmental preservation work: ‘Let the mountains talk, let the rivers run’.

In 1986 Brower resigned as the head of Friends of the Earth, but meanwhile he had founded another organisation with a US brief, ‘The Earth Island Institute’. This is still like the other organisations he had given his effort and direction to, going on from strength to strength as is the David Brower centre in Berkeley. He died in 2000, but not before he had been invited back twice onto the Board of The Sierra Club. I met him once at an event organised by the American Alpine Club in Colorado in the 1980’s, he was tall, with an impressive presence and a very inquisitive look for all around him. When I was introduced to him by an old friend, a former President of the AAC, Bill Putnam he looked at me for a moment and demanded to know what was happening ‘to conserve the mountains of Snowdonia?’ He was as we might say in Yorkshire ‘an old cough drop!’

Amory Lovins

Amory Lovins is in a long line of scientist mountaineers; born in Washington D C in 1947 he began his academic career at Harvard, but moved to Oxford University to study Physics in 1967. He had already started mountaineering in the White Mountains of New Hampshire before that and each summer from 1965 Lovins guided trips there, earning a reputation as a photographer and essayist. At Oxford he joined the University Mountaineering Club, and contributed articles to its journal, including a contribution in 1969 about some of his Appalachian mountain activities entitled ‘New England Wanderer’, and whilst in the UK he became enthused by the hills of Snowdonia, and in 1971 this led on to the publication of his first book, ‘Eryri, The Mountains of Longing’, with photographs by Philip Evans and a foreword by Charles Evans. This put him in touch with Dave Brower and The Friends of the Earth who edited and published the book in their Earth’s Wild Places series. This volume is now a collectors-item, including poems and excerpts of writing by many other authors including R.S.Thomas to W.H.Murray with a mountain/wilderness theme. For some years he stayed on at Oxford gaining an M.A and becoming a Don, but then he was persuaded by Brower to become the first overseas employee of Friends of the Earth, and so he left academia and moved to London where he stayed until 1981.

In my early years at the BMC in the 1970’s we were hard wired into developing our policies over conservation and access, for we were often faced with threats both by access problems and inappropriate development schemes. In 1973 the World Energy crisis focussed our thinking about its generation, especially potential further Hydro schemes in the hill regions of the country. Alan Blackshaw was a high powered civil servant, the Under Secretary for Energy no less, and was later to be responsible for the bringing in of North Sea Oil. He was also the BMC President. Lovins had begun to specialise in the energy field, and I can remember Alan suggesting we try to get him involved, and so we welcomed him to advise in this area. He was very easy to know, and looked like a stereotypical Professor with a studious aspect that belied a fine sense of humour.

Amory returned to the USA in 1981 and in the following year he established with his wife Hunter Lovins, The Rocky Mountain Institute in Snowmass, Colorado. There he developed his theories of a ‘soft energy path’, based on efficient energy use, and also utilising diverse and renewable sources; wind, solar etc. It all reads as standard thinking now but in 1982 this was revolutionary. To promote his ideas he made with his wife ( a photographer) a film documentary that won awards and he began a series of books to follow this up, some of which became best sellers, ‘Reinventing fire’, ‘Small is Profitable’, ‘Natural Capitalism’ and as of today he has now published 31 volumes in all. A volume of his selected essays, ‘The Essential Amory Lovins’, covering every subject from climbing to research physics was put together by the well known mountaineering commentator, Cameron Burns in 2011, and it was published by The Green Library.

His ideas are now centre stage, influencing Al Gore and other major public figures and he is so weighed down with awards and recognition, so much so that I will only, note that he has so far received ten honorary doctorates, two medals-The Benjamin Franklin and Happold medals, and dozens of other awards (The Heinz, Nissan, Lindbergh etc). In 1994 he started to work on ideas for improving and developing more energy efficient cars, which led to the Hypercar which was hydrogen powered, his ideas have led on to the major motor manufacturers bringing out a range of hybrids, including both BMW and Volkswagen.

He has now worked in the area of energy policy and its related fields for four decades, including advising several overseas governments to help develop their policies in this field. In 2009 he was named by Time Magazine as one of the World’s 100 most influential people. The lad has come a long way from his youthful scrambling along the Grib Goch Ridge many years ago, and so the last words might be to any young climber just setting forth on their first tentative climbs; think where an awareness and respect for the mountain environment might- just might lead you?

Dennis Gray: 2017: Previously Unpublished

Helyg

At the end of a month of glorious weather in August 1939, when the only clouds were those of impending war in Europe, My wife Joy and I were walking with the Lake District artist Heaton Cooper, down Far Easedale, after a relaxed day's climbing on Lining Crag, below Greenup Edge. Only the day beforehand I had received a telegram, awaiting on our return to the Old Dungeon Ghyll from a day spent climbing on Gimmer Crag. I was instructed to report at Greenock on 2nd September, only three days later, to join the first troop convoy of the war.

I was due to sail on 3rd September, the third anniversary of our marriage.We strolled down the dale with a deep sense of things ending; of parting and uncertainty about the future. I recall saying to Joy: "Whatever else changes, these hills will still be the same when it's all over."

Self-evident though they were, these words implied the fun we had enjoyed during July and August of that year. We had rented a bungalow at Braithwaite, and later taken a cottage in Grasmere, after returning from India. Our stay in the Lakes had been intended as a retreat from my studies for the Army Staff college exams. But as the days passed, bringing war even closer, that work became ever more irrelevant. In fact, we spent everyday climbing during those eight weeks; I still have the long list of climbs we did during that run-up to the declaration of war. The prospect of an end to those happy days, and to other days spent in Snowdonia during our three years of marriage, weighed heavily on our minds on our way back to Grasmere.

As things turned out, I had a rather good war as far as the mountains were concerned. I ran a training course at Helyg for members of my Brigade, and trained Commandos to climb in the Cairngorms and Snowdonia, and overseas there were times spent on Olympus, Athos and in the Appenines. There were opportunities to ski in the Vermion mountains, in the Peleponnese and on the hills surrounding Athens. But most memorable were the brief opportunities to return with Joy to the Lakes and North Wales during spells of leave from abroad. The first of these occasions was, to say the least of it, unfortunate. I had returned from India during the summer of 1940, and our first chance to return to the hills was in December of that year. We were expecting our second child early in 1941, so Joy would not be climbing and we would not go far afield.

We decided to spend the day following our arrival at Ogwen Cottage in the area surrounding Llyn Bochlwyd. It was one of those rare mid-winter days, with a clear sky after an overnight frost. Aware of my lack of form after 12 months since I had last climbed; conscious, too, of my forthcoming paternal responsibility, I resolved to do only a few modest climbs. I soloed happily up several routes on Bochlwyd Buttress, and moved on up to the Alphabet Slab on Glyder Fach. Beta and Delta presented no problems. It was now past mid-day; time to rejoin Joy, who was patiently waiting for me beside Llyn Bochlwyd. Should I do one more climb?

With growing confidence I started up Alpha. All went well until I reached the final pitch, which I remember as requiring a pull-up on small holds from an exiguous stance. Alas! I lacked the strength to make it. With a sense of resignation about the inevitable outcome, I lowered myself gingerly to the small ledge where I had stood. Once again I tried to pull up, yet knowing the hopelessness of it. This time toes failed to find the stance, and I was 'off'. I fell.... the grey rock flashing past my vision like the walls of a lift when you descend to the basement. There was no sense of fear. I felt — or was aware of — a terrific bang, before floating into nothingness. I had fallen 100 feet before hitting the screes, and may have rolled a few more yards down the slope. Close by were the rucksacks of a CUMC party who were engaged on the Direct Route. They found me a further impediment to their baggage when they returned from their climb.

Eventually help arrived from the valley in the persons of a policeman and a doctor from Bethesda; mountain rescue was not an organised business in those days. With the Cambridge party acting as carriers of the stretcher which had been brought up from below, and with Joy in close attendance, we descended to the road. So much for paternal responsibility! A year later, in December 1941, I had recovered from the accident and we were again staying at Ogwen Cottage. Once again it was a perfect winter day when we prepared to start out on what, in view of the limited daylight hours, was a somewhat ambitious programme. We proposed to cross Bwlch Tryfan on our way to Lliwedd, climb the East Buttress via the Avalanche Route, traverse Snowdon, Crib y Ddysgl and Crib Goch and return to the cottage: all this was on foot, of course, for we had no car in those days. This time we had a companion. Marco Pallis was a climber with Himalayan experience; he had climbed in Sikkim with Freddie Spencer-Chapman. He had also led an expedition to the Gangotri area of the Central Himalaya in 1933.

Llyn Bochlwyd

He was also a competent rock climber, who had pioneered Birthday Crack on Clogwyn du'r Arddu with Colin Kirkus and Maurice Linnell. From his Himalayan experience he had adopted the Buddhist faith which, I suspect, had some bearing on our fortunes during that December day; he was imperturbable and oblivious to the passage of time.

Joy and I had planned an early start, but Marco arrived very late and it was mid-day before we were able to leave the cottage. It took us three and a half hours to reach the foot of Lliwedd. Marco was out of practice and unfit, so we made slow progress on the climb. By the time we had finished the route we were in total darkness, and had some difficulty in climbing the easy Terminal Arete. On the summit of the East Peak, having no torches, we were in real trouble. To continue over Snowdon and along the Horseshoe ridge was out of the question. Indeed, so minimal was our vision that we resorted to crawling on hands and knees, hopefully heading for the scree gully leading down to Llyn Llydaw, anticipating disaster from a fall over some minor crag on our way. During the descent Marco sprained an ankle, making progress even more snail-like.

At Pen y Gwryd we had a stroke of luck when we met a member of the Home Guard coming out of the hotel, who gave us a lift to Capel Curig. Here, by another fortunate coincidence, a good samaritan appeared in the person of Ifan Roberts, a local quarryman and botanist who was to become a good friend to myself and many other climbers. He was on his way home after duty as a member of the Observer Corps and he, in turn, gave us a further lift to Ogwen Cottage. It was nearly 2am. Great was the relief of Mrs Williams and her daughter, who were just about to report our absence to the police. I recall that episode with affection and respect for Marco Pallis, whose serenity and patience throughout the expedition was an object lesson to myself. And there were other friends who joined us during further visits to Snowdonia, before I was again posted overseas in 1943.

Indeed, our climbs, enjoyable though some of them were, were less important than the company we kept. I remember a splendid day in the Great Gully on Craig y Isfa with Alf Bridge. Alf, a perfectionist, was a dynamic and loveable character, who resigned at various times, from both the Climbers' Club and the Alpine Club on matters of principle, but remained a close friend of many climbers. He had helped me run the training course at Helyg and was later to play a vital role in the assembly and dispatch of our oxygen equipment on Everest in 1953. I recall a much smaller climb with Wilfred Noyce during that Helyg course: on Chalkren Stairs, Gallt yr Ogof, when he, a brilliant rock climber, 'came off' while climbing the final slab, and I had the privilege of holding his fall and then giving him a top-rope! During the Commando courses I enjoyed the company of Frank Smythe of Everest 1933 fame, and David Cox. Frank, a gentle and most unwar-like person, was commandant of the Commando and Snow Warfare school. He was a member of the party which made the first ascent of Longland's on Clogwyn du'r Arddu; but he, like Marco, was no longer in his prime on hard rock.

1963 Everest reunion at the Pen yr Gwryd

With David Cox I did a number of climbs from our Commando Training base at Braemar. I also recall a very pleasant route we did on Craig yr Isfa, in the Arch Gully area of the crag. For David, Wilfred and myself, those years marked the beginning of a very happy partnership after the war, in Britain and in the Alps. With Wilf, that shared experience later extended to the Himalaya and the Pamirs. I remember how peaceful were the hills in wartime.

How remote they were from the global conflict. In Snowdonia, the roads were narrow and winding in those days, bordered by the ancient dry stone walls and burdened by a negligible flow of traffic. No tourist industry brought visitors in their thousands at at weekends to the 'honey-pot' areas of Beddgelert, Capel Curig, Betws y Coed, Pen y Pass and Llanberis. There were few climbers or walkers around. Apart from mainly sea training orientated Outward Bound Centre at Aberdovey, no activity centres had been established, to add their colourful anoraks to the scenery and to create congestion on the more popular climbs. Plas y Brenin was still the historic Royal Hotel. At Pen y Pass, the Gorfwysfa Hotel, famed for the reunions convened by Geoffrey Winthrop Young at Easter, was still in business.Ogwen Cottage was still a humble inn for the likes of Joy and me.

The mountains were not under threat from new hydro-electric schemes or other equally unfriendly development. There was no perceived need for planning controls; it would only be a decade later that the Lake District and Snowdonia would be designated as National Parks. When we were able to return to those hills in 1946, the words I spoke on the way down from Far Easedale on that glorious evening at the end of August 1939 were still true.....'These hills will still be the same when it's all over."

John Hunt: First published as 'Some memories of climbing in war time' in the CCJ 1995

Image: Glenn Denny

It may seem a strange thing to say, but Royal Robbins carried British climbing values into American climbing culture with permanent benefit for both climbers and the rock they climbed. There were to be no more peg scars in Yosemite cracks, which now became finger locks for climbs protected by nuts, and bolt ladders became the guilty ‘machine in the garden’, to use Leo Marx’s famous phrase, that they always had been. So when he came to the UK, often at the suggestion, behind the scenes, of Ken Wilson, Royal reflected back at us, in his gracious, principled, quiet, steely manner, our own best selves, in case we had forgotten and had started bolting beside cracks in quarries like Harper Hill.

It was his mother, who moved to California when he was a teenager, who taught Robbins self-reliance – breaking through low self-esteem at school, the disappearance of two fathers, an attempted robbery - and it was the Boy Scouts that introduced him to rock climbing in the High Sierra. He wrote in the first volume of his autobiography, ‘Scouting is a vehicle through which good men change forever the lives of boys, and are forever remembered for doing so’. Bouldering and top-roping after school at the local sandstone outcrops at Stoney Point, Robbins gained his first lessons and a broken wrist.

In 1952, Robbins made the first free ascent of the Open Book in Tahquitz, California, pushing free climbing standards to 5.9. Five years later, he, Jerry Gallwas, and Mike Sherrick completed the first ascent of the Northwest Face of Half Dome over five days. But it was the 1967 ascent with his wife Liz of The Nutcracker (5.8) in Yosemite, after a visit to the UK had convinced him that pitons could be replaced by nuts, even on a 500 foot route, that changed everything. Warren Harding had been sieging and bolting his way up Yosemite’s walls, sometimes with six months gaps between pitches for weather and partying, and Robbins was determined to demonstrate that there was a better way.

As his partner Tom Frost said, ‘His philosophy was that it’s not getting to the summit but how you do it that counts’. Harding declared that Robbins was the ‘Valley Christian’ in his advocacy of ‘clean climbing’. Perhaps nowhere was Robbins’ preaching more eloquent than on the West Face of Leaning Tower, which had taken Harding seventeen months to climb with the use of fixed ropes from bottom to top, and multiple partners, topping out in November 1958. Four and a half years later Robbins soloed the route over four days, using some of Harding’s bolts, but cleaning his pitons after each pitch (five years before he discovered the even cleaner use of nuts).

This was the ‘Golden Age’ of Yosemite climbing, but during this period Robbins also applied his approach in first ascents on Alpine walls elsewhere, such as his 1962 first ascent of the American Direct (ED: 5.11, 1000m) on the Aiguille du Dru with Gary Hemming, and the 1963 first ascent of the Robbins Route (originally VI 5.8 A4) on Mt. Proboscis in Canada's Northwest Territories with Jim McCarthy, Layton Kor and Dick McCracken. It was in Yosemite, however, that Robbins forged his climbing ethics.

In 2010 Robbins reflected, ‘I think that we were drawn to our ethical stance because it was harder that way, frankly, and I think whatever’s harder has to be better’. In later life Robbins admitted to really being in thrall to ‘the fame dragon’ as much as Harding and admired his sheer grit in staying focussed on his routes. Harding had answered Robbins’ Half Dome ascent with the epic first ascent of The Nose of El Cap, bolting the last pitch with desperate determination through the night. Robbins replied with the first ascent of the Salathe Wall with Tom Frost and Chuck Pratt, taking a natural line that required only thirteen bolts, before Harding did Leaning Tower. Robbins’ second ascent of The Nose was made in a continuous, seven-day push with Joe Fitschen, Chuck Pratt and Tom Frost.

A more radical statement was made in Robbins’ second ascent of the Wall of Early Morning Light on El Cap in 1971 with Don Lauria. Robbins was outraged at the first ascent made in typical Harding siege style, later writing: ‘Here was a route with 330 bolts. It had been forced up what we felt to be a very unnatural line, sandwiched between other routes, merely to get another route on El Capitan and bring credit to the people who climbed it. We felt that this could be done anywhere; instead of 330 bolts, the next might have 600 bolts, or even double that. We felt that it was an outrage, and that if a distinction between what is acceptable and what is not acceptable had to be made, then this was the time to make it.’ Probably the TV appearances Harding made as a hero of Yosemite climbing had something to do with Robbins and Lauria making plans to remove the route, chopping the bolts off the wall as they climbed.

Their six day climb also became the first winter ascent of El Cap. When Geoff Birtles cheekily asked Robbins to write Harding’s obituary for High magazine Robbins rose to the occasion with honesty, grace and wit, recalling his last visit to Harding in his hospital bed where, as Robbins was leaving, Harding looked up at the tubes coming into his arm and said, ‘More wine!’ After arthritis curtailed his climbing career, Robbins made many kayak first descents in the Sierras after he realised that some were only possible in meltwater floods. This included the ‘Triple Crown’ of the last three great rivers in the Sierra that had yet to see a descent. In 1967 Robbins launched a climbing-gear company, importing boots, ropes, and helmets with his wife Liz who was his real rock. By the 1980s, this small gear company, Mountain Paraphernalia, had blossomed into a business producing no-nonsense, reliable clothing, called ‘Royal Robbins’ which, although they sold it in 2003, is still going strong today.

Robbins also became known for his classic instructional books Basic Rockcraft (1971) and Advanced Rockcraft (1973) which taught the techniques of clean climbing. Robbins even included a ‘Sermon’ in Advanced Rockcraft in which he summed up his ‘rules’ of climbing: stay safe, be honest, and leave the stone unchanged. More recently the three published volumes of his autobiography reflect wryly on the philosophy behind his statement climbs and generously acknowledge his debts to his mentors, protagonists and partners.

It was sad that Robbins was probably unaware of the earlier death of his old friend Ken Wilson because, like Ken, he was suffering from dementia. I heard of Robbins’ death in an email from my Californian climbing partner, Larry Giacomino, who expressed the feelings of a local: ‘A really sad day for us here. He was a cut above the rest of us in terms of ethics - a couple of cuts above in skill. And his judgement was impeccable. I must go to his “Camp Four Wine Café” in Modesto on my next trip to the Valley.’ Royal Robbins had a Camp Four Wine Café? Had he stolen one idea from Harding after all?

Terry Gifford: 2017. First Published in Climber-April 2017

As a tribute to Walt Unsworth who died on Tuesday at the fine age of 89, the following article is a piece he wrote for Climber magazine in 1983 when he was editor. His long and active life in the world of mountain literature as an author, editor and publisher, can be discovered in fuller detail in the linked Cicerone appreciation at the foot of this article.

Everyone has their own favourites amongst the lesser hills of Britain; places to which they can return time and again, not in the expectation of a dour struggle against mountain and weather perhaps (though sometimes they surprise you) but for spiritual renewal, in the way that the old mill workers used to tread the draughty Pennines. My favourites have always been in my backyard, so to speak. When I lived in the Midlands I found much pleasure in tramping the Stiperstones and scrambling about the weird, witch-begotten rocks that mark the top of that strange hill; when I lived in Manchester the Anglezarke moors became a favourite and I remember particularly one long winter's walk with A. B. Hargreaves and Jim O'Neil, staggering down in the frosty darkness to a hotpot supper at Rivington Old Barn.

Nowadays my favourites are the Howgills which I can just about glimpse from the look-out on the roof of my house, put there by a long dead sea captain, who wanted to see the ships coming into Sandside. He traded in slaves, incidentally. The Howgills are, for me, the very essence of Housman's 'blue remembered hills' — much more so than the others I've mentioned. They are hills as a child would draw hills: steep sided cones clustered together in a broad clump. From a distant viewpoint like Farleton Fell they often seem literally blue, or more accurately perhaps, a pale mauve — then the light will change and a hint of green show through, dappled by shadows from passing clouds. I first saw these hills as a child during the war when I was periodically shipped off to Edinburgh out of harm's way. The gorge of the Lune was always one of the highlights of the journey, the great steam locomotive of the L.M.S. charging into the narrow dale, cinders flying from the smoke stack and the steep sided hills crowding in on either hand. They made a marvellous picture framed by the carriage windows and, strangely enough, that same view of the Howgills is still the best, in my opinion. Though nowadays it is more often viewed from the adjacent motorway, where the view is wider

and more long lasting.

Thousands of travellers over the years must have had their curiosity aroused by the conspicuous gash of Carlin Gill which is the focal point of this scene. Perhaps some, like Hassan, went a little further and determined to someday penetrate the Gill, looking for the last blue mountain. Though not many, I think. The Howgills are never overpopulated despite the fact that they have a Wainwright guide, not to mention a Harvey large scale map. They are not to everyone's taste- thank God- being, as someone once said, neither 'fish nor fowl'. Meaning that they had neither the rugged grandeur of the Lakeland fells which flank them to the west, nor the bogtrotting bleakness of the Pennine moors to the east. The qualities they possess are their own. Exceedingly steep slopes and a short, dry, springy turf which makes walking a pleasure. They are by no means gentle hills, but neither are they savage in the way that, say, Bleaklow is. Technically, I suppose, several of the tops in the Howgills are not hills but mountains, if one accepts the generally agreed definition of a mountain as something of 2000ft or over.

The highest point, The Calf, is 2219ft: Randygill Top, Yarlside, Fell Head, all make the magic mark, though ‘nobbut just' as they say, whilst most of the others miss out by the merest of margins. Nor are they hills in another sense: they are of the North West and therefore `fells', in the proper Norse tradition.

My first excursion into the Howgills, like that of many walkers, was to climb The. Calf from the Cross Keys temperance hotel at Cautley. It has the advantage of superb scenery insofar as it gives close views of the gaunt and crumbling Cautley Crag and that celebrated showpiece of the district, the waterfall of Cautley Spout. It has the disadvantage of being short and steep if you take the most direct line and intend going no further than The Calf. Both objections are easily overcome. The first visit began inauspiciously, I remember. Somebody had put a bull in the field at the bottom of Cautley Holme Beck. It was necessary to pass quite close, and my thoughts, which should have been on the beauty of nature, were on whether it was possible to run up Yarlside carrying a rucksack and the folly of wearing a red cagoule! Fortunately the bull just stared at me balefully.

I've never seen one there since, I'm glad to say, especially as these days I know I couldn't run up Yarlside. On this walk the best way to reduce the overall steepness is to climb the slopes to the col at Bowderdale Head, between Yarlside and The Calf, then continue in the same direction to an obvious slanting trod which circles round the flanks of The Calf to the summit plateau. The Spout is the main feature of the walk, without doubt. It is really a string of waterfalls in two main sections, looking like a silver ribbon carelessly tossed down the fellside. It is attractive, impressive — far more so than any waterfall in the Lakes- and comparable with The Grey Mare's Tail near Moffat.

This walk can be lengthened by continuing over Bram Rigg Top, Calders and Great Dummacks, then descending the steep fellside back to the Cross Keys. I once did this on a meet led by John and Fredda Kemsley, who had the happy knack of organising club meets in the lesser known hills. The previous day we had been over Wild Boar Fell and Mallerstang Edge in hot weather, with ABH searching for a suitable pool in which to have a dip, en route. Sadly, John and Fredda were to lose their lives a couple of years later in a storm on the Dent d' Herens.

There is a more energetic approach to The Calf from the Cross Keys which Pat Hurley and I took one time and which visits some of the less frequented eastern tops. We began up Westerdale, crossing the Backside Beck by a little footbridge, then following the old farm road which leads from Narthwaite to Mountain View. This is a short valley by Howgill standards, so before long we were climbing up to the col below Randygill Top and following the fine little ridge that leads to the summit. What an extensive view there is from this fell! In the distance the blue ridges of Lakeland sweep across the horizon from Coniston Old Man to Carrock Fell. Cross Fell rises massively to the north, then, turning in a half circle eastwards, we could pick out Wild Boar Fell, Ingleborough, Whernside and the tangle of fells around Barbon. The nearer view, too, is impressive, especially the long trough of Bowderdale which lay directly below us. The ridges and deep troughs of the Howgills were revealed in their complexity; hump upon hump, like a shoal of stranded whales. The slopes of our next objectives, Kensgriff and Yarlside, looked horrendous as they shimmered in the hot sun.

The way ahead, as we knew it would be, turned out to be a very up and down affair, like walking the track of Blackpool's Big Dipper. You've simply got to get used to the steep fellsides if you are to enjoy the Howgills at all, and few come steeper than the traverse from Randygill Top over Kensgriff and Yarlside to the col at Bowderdale Head. The ascent of Yarlside in particular is a real cruncher, like climbing Whernside from Greensett Tarn. Yarlside does have one advantage, however, which even Wainwright seems to have missed. Descending from the summit to Bowderdale Head (another steep knee jerker) gives the best views of Cautley Spout you are likely to see.

From the col we plugged our way up to The Calf by the usual route then, in descent, followed the beck down to take a closer look at the Spout — not, I hasten to add, a recommended thing to do and certainly not if the weather is bad. That evening we ate at The Fat Lamb. Peering out of the window we thought the sun and the steep slopes had finally done for us and brought on hallucinations. Peering back at us was a llama, of the Peruvian kind. "Oh, my God," I cried. "We've flipped at last!" "It must be the ale," said Pat, who is a doctor and should know about these things.

It was, of course, Henry, the landlord's pet llama. Carlin Gill is different from any other walk in the Howgills. From the narrow road the Romans built along the western flanks of the fells you enter at once into a narrow valley which twists away to the right. So steep are the valley sides that landslip is common and the grass has at best a tenuous hold on the shaley slopes. The path crosses and recrosses the beck, seeking what footholds it can until at last the valley widens at a confluence and makes a splendid camp site. Beyond this it narrows again to a small rocky gorge where the best way ahead is usually the bed of the gill, though in a really wet season this might not be practicable. Once through the narrows, the gill divides in a dramatic manner.

The main stream comes directly down from a splendid little waterfall, known, somewhat confusingly, as The Spout. It is set in a craggy bower, bypassed on the left by extremely steep shaley slopes, the like of which I wouldn't recommend even to a mere acquaintance. The Spout is fine, but is overshadowed by Black Force, a deep ravine which tumbles into the gill on its right bank. There is a scramble up the bed of Black Force which Brian Evans mentions in Scrambles In The Lake District, but most walkers would prefer the fine, steep, grass ridge which bounds it on the left. Pat Hurley and I were here once when the mist was low, giving the head of the gill a Wagnerian atmosphere. Fingers of vapour drifted in and out of Black Force, making it appear much more savage than it really is.

We were very impressed and even more impressed as we crawled up the narrow ridge, the top of which seemed like a miniature model of Halls Fell on Blencathra,with nothing but bottomless pits of mist on either hand. Pure illusion, of course — take away the mist and you have a straightforward slog offering interesting views into the Force. On that misty day we traversed, somewhat uncertainly, over Fell Head and round the ridge over White Fell to The Calf. The compass seemed unreliable, for I tend not to trust an instrument which gives me three different directions for North whilst I'm standing still, and it may be that there are magnetic influences in the underlying rock, though nobody else seems to have noticed them.

Walt Unsworth: Cicerone Press

Anyway, I kept the compass in my pocket as a good-luck charm, and steered by God and Guesswork, as the old mariners used to say. There were never enough windows in the mist to give us a clear idea of where we were at any one time, but somehow we managed to reach the trig block on The Calf without too much fuss. On the descent, naturally, the mist began to rise and we had a splendid jog down the long ridge of White Fell to Chapel Beck, then cut steeply over Brown Moor and the slopes beyond to reach the Fairmile Gate on the Roman Road. Steak and chips at the Barnaby Rudge in Tebay, washed down with a couple of pints of good ale, ended what had been another memorable day on the Howgills. ■

Walt Unsworth: Climber November 1983

Cicerone Appreciation article

I got to know the Tremadog cliffs in 1953 when the Birmingham Cave and Crag Club (of which I was a member) bought Pant Ifan, a traditional Welsh cottage on the plateau above the cliff of that name. We found the cottage on our first trip to the crags when we did a new route by mistake, a common occurrence at Tremadog in those days. I became even keener to go there at weekends after acquiring a Welsh girlfriend called Blodwyn, who worked in the gunpowder works at Penrhyndeudraeth. Her previous Welsh boyfriend had "blown" off the scene owing to an explosion at the factory and I got her on the rebound. The charms of Blodwyn were all very fine but were mainly nocturnal and I had to do something else during the day.

As the cliffs were almost completely untouched new routes became essential to maintain the interest so we set about doing some. Ray Handley tried to do Barbarian one wet day. He took a poor stance with a mediocre peg belay and when my wet P.A.'s slipped I hurtled past Ray, who was pulled off his stance although he managed to hold me. The peg bent completely over until the eye touched the rock and then grated outwards half an inch before mercifully stopping.

After every new route we used to have a celebration; on one occasion we decided to have a drink in every pub in Porthmadog, thirteen there were I think. We just made it back to the hut, where there were some staid sober members seated at a table with a full bottle of whisky on it. I grabbed it and took several gulps. They neglected to tell me that it contained detergent. The bubbles, froth and pain were quite enough until a couple of hours later I also realised that detergent was also a laxative, causing symptoms which are far too disgusting to relate in a magazine as pure as this one.

In the middle fifties I got involved with the Rock and Ice and did new routes with one J. Brown. They used to make early starts because Mortimer the apprentice was the mobile tea-making machine and had the quick method of sucking the condensed milk out of the tin and spitting it into each cup. Everyone knows that I fell off the first ascent of Vector before an admiring throng of 50,000 Joe Brown hero-worshippers.

I was ignominiously lowered to the ground amidst a whirring of cine-cameras, a climax to yet another Brown extravaganza. Pete Crew and I made the second ascent of Tensor after several people had been gripped trying it. I had forgotten my climbing clothes and had to climb in my best suit and unfortunately ripped the trousers badly. This major crime had to be confessed to my wife on getting back to Manchester and this has resulted in a close examination whenever I put on my "bezzies" for signs of abseiling, gardening, resin or chalk. Any signs of these on or in suits cause a mandatory two-week silence.

I had done some sea cliff climbing during my National Service in 1949 when I was an R.A.F. officer, although not a gentleman. I was stationed for a short time at Valley on Anglesey where there were some practise cliffs with a standard set of hard routes. The hardest of them was called "The Wicked" which needed a sling and a special chockstone which was kept in the equipment stores which was signed for and drawn out before an ascent was made. I soloed the route without the chockstone and threw it away; an early example of reducing aid I suppose. Many of my new routes were done with Harry Smith, a prehensile plasterer of enormous strength, who always climbed in a pair of decrepit curly-toed spog boots.

He had a very good collection of firearms and when elated or full of the joys of spring would blast off a few dozen bullets at the nearest target. He taught me how to climb hard and to break through the magic XS barrier. We discovered that we could climb hard at Tremadog all winter and so were very fit for the following summer season. But always after the Alps or even the Himalayas we always went back to our quiet Tremadog crags, where we were the only people on them in those far off days, when I was very young.

Trefor Jones: First Published in the CCJ 1976