Milky sunshine heralded our first morning on Lundy, after we had travelled over the previous day on the Oldenburg. Unusually (for Mick Wrigley and myself) it was an easy and uneventful crossing from Ilfracombe on a virtually flat sea. It was well into October, but it was a warm, sunny morning and the journey was enlivened by the antics of numerous Gannets and Petrels flying close to the boat in the gentle swell. Late that afternoon we abseiled down the Old Light Cliff, and dashed up the old classic Albacore before it got dark.

The top part of the route is pretty grotty and we were glad that the abseil rope was at hand, but the main pitch was every bit as good as I remembered from twenty years ago. We returned to this crag later in the week and Mick led Asafoetida, an absolutely top class Extreme, with a superb 5b pitch on immaculate rock. This first evening we wandered back past the Old Light to the doss, in the dark, the wind coming optimistically firmly from the east. A clear sky seemed to bode well for Sunday and indeed the next few days.

After the usual "boys away from home" breakfast, we sorted the gear and set off for somewhere new. Mick and I had visited Lundy a number of times but had never climbed at the extreme north end on the crags close to the North Light. The walk over the island, across the three walls, is always a pleasure and on this increasingly bright autumn morning it was particularly so. It felt good to be back at this lovely place and there was not another person to be seen all the way to the lonely northern end of the island. The further we went, the more goats we saw, dozens of them, many with impressive sets of horns.

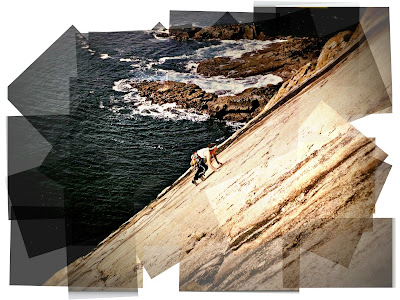

Diamond Solitaire: Ken Latham

The walk to the North Light took about forty five minutes and by the time we got there it had clouded over a little. The sea was relatively benign by Lundy standards and there was just a gentle breeze. The route we had gone to climb was The Pearl, a single pitch Hard VS rumoured to be excellent. Access to the top of the buttress alongside Storm Zawn was simple enough and a straightforward 100ft abseil soon saw us next to a beautiful rock pool just above sea level, at the foot of the route. From where I stood The Pearl looked bloody steep (even for Lundy 5b) but Mick was soon uncoiling the ropes, raring to go for it. He tied on and set off boldly up a very steep little groove above me. The protection was good and despite complaints of dampness in the main corner of the pitch he was soon tied on at the top.

As Mick was climbing I paid the rope out with care, lashed to sound nut belays. I took the opportunity to look out to sea and to watch the numerous large seals that had swum round to take a look at us. (Lundy does a good line in very large seals. These were the largest I've ever seen in Britain.) At one point, I was watching my hands as I paid out the red and yellow ropes through the belay brake, when suddenly the sun came out and bathed the granite wall in golden morning light clearly picking out the complex texture of the ancient Lundy granite. It was a superbly lonely spot, no-one knew where we were and it felt as isolated as anywhere I've been in the south-west (the foot of Carn Gowla in a big sea is perhaps the only contender.)

The pitch was hard but fair, fingery on the crux with some unwelcome dampness just where it mattered and an energetic layback exit to complete an uncompromising little number that quite tired us both. The rest of the day was spent in a more relaxed manner. We had a quick stroll up Albion (surely one of the best VS routes in Britain) and then moved over to the foot of the Cheeses. The afternoon was well on and the day was developing a lovely October feel to it. We abseiled in and rounded the day off with Pete Thexton and Ken Wilson's gem Immaculate Slab. The sea was dead flat and the perfect granite of this superb climb was bathed in a gorgeous autumnal ochre light. As Mick said, you could do that route every weekend and never tire of it. It was growing darker as we sorted the gear at the top of the crag and a hint of drizzle livened up the gentle walk back to the doss and then the pub.

Later in the week the sunny weather deserted us for a while and one morning in particular dawned very dull and dismal, though fortunately without rain. The wind had got round to the south but the sky was brightening slightly so we packed the sacs, threw in the big abseil rope and set off past the Old Light and along the cliff top path. We crossed the Quarter Wall and carried on until we were above Deep Zawn. Here we considered the moot point of the weather (i.e. was it going to piss down or not?) Meadow Pipits scuttled around in the grass near us, while away to the south we could hear the regular crack of rifle shots as the annual goat culling got underway. We decided to take a gamble with the weather and abseil into Deep Zawn and climb The Serpent. I found a bomb-proof pair of thread belays in the boulders above the zawn and Mick abseiled in down the seaward face.

As soon as the rope went slack, I clipped in and followed him down as I slowly descended I took in the surroundings and they were mighty impressive. The zawn itself cuts deeply into the hillside above, the walls are plum vertical for over 200ft and the distance between the South Wall and the North Wall is probably no more than 70ft. On this particular morning, the place was particularly dark and oppressive albeit with a flat sea, but with the sky rapidly darkening out to the west. I am susceptible to the atmosphere of places I admit, but this was something very special. It was my first visit to Deep Zawn and the primeval character of it was only too obvious as I looked across the dark, sinister water to the gob smacking lines of Gracelands (E6) and Underworld (E3). Just around the corner were Stone Tape (E3) Quatermass (E2) and the truly awesome looking Supernova (E5). I marvelled at the strength of mind and sheer courage of Pat Littlejohn and his mates in venturing into this place in its initial development, and there are few locations in the south-west as intimidating as this.

As we sat there the sky continued to darken and the sea started to get rather more lively. The vertical walls of shiny green granite plunged straight into the waves, while as you looked out from the zawn there was nothing but wild ocean for 3,000 miles, to the shores of Nova Scotia. Today the swell on the sea was gentle, but sometimes it must be an utter maelstrom in that dark confined space, a cacophony of rain, waves and gale force wind. I shuddered at the thought of it there on a dark, moonless night when all the malign forces of wind and sea are unleashed from the west. Apart from our blue abseil rope, there was not the slightest indication that mankind even existed in this place.Place yourself there, ten thousand years ago and it would look no different, the only creatures are the birds and the seals, it is truly their place and I almost felt we were intruding.

Just to add to the increasingly oppressive atmosphere, strange sounds were coming from the back of the zawn; howls and almost dog-like yelps echoed off the walls. I realised that this was of course adult seals mating, and sometimes fighting. These strange sounds were juxtaposed with the continuing crack of the rifle shots on the moors above us, as the goat culling continued. The combination of these two sounds, the oppressive character of the zawn itself and the increasingly threatening weather was quite unsettling. For a few moments, I really felt as if we shouldn't be there, that we were not welcome and that we clearly did not belong there. There were no other climbers on the island and no one had a clue that we were here in this deeply impressive place. From Deep Zawn north to the Devil's Slide is perhaps only ten minute walk but a greater contrast with the white, sun-kissed granite of The Slide would be hard to imagine.

I unclipped from the abseil rope, having fixed a secure belay looking into the zawn. Mick and I started to sort the gear out, when suddenly the sky darkened some more and the heavens just opened. It absolutely poured with rain, drenching our route (and everything else!) We waited awhile to see if it would relent but if anything it got worse. I watched Mick prussic out up the abseil rope as mist rolled in off the vastness of The Atlantic. Below us the seals were still howling, while above us they were still busy goat killing. I clipped the prussic clamps onto the blue rope, took a last look around, stepped up, slid the clamps up the rope and started the journey out of the zawn.

Mick plods slowly up the hill with all the gear, while I haul in 200ft of wet (heavy!) abseil rope and the weather sets in for the day. We are both wet through, but the trip into Deep Zawn had been strangely satisfying for me. Neither Bosigran's Great Zawn, or anywhere at Gogarth or Pembroke could compare with the lonely desolation of this place particularly on an atmospheric late autumn day. We sorted the gear, shouldered the sacs and strolled back for a pint in the pub. As I said though, certainly not a wasted day and a glimpse of just how wild some of Lundy's west coast is. Later as the rain hammered on the pub windows, I thought again of the birds and the seals at home in Deep Zawn and wondered if we were the last people to go into that place this year.

Every evening we make the walk down the hill to the warm embrace of The Marisco Tavern, for a few pints of Old Light Bitter. This is a splendid drop brewed at St Austell and a world away from the days of the infamous Puffin Bitter thought by some harsh observers to be brewed from sea water! Most nights the pub is cheerfully busy, with plenty of friendly chat and a guitarist and mandolin player in the corner of the bar giving it a traditional feel. It is very late in the season (third week in October) and we are the only climbers on the island. However, the bird watching lads are out in force, with bird books and laptops on the bar tables. Their often serious and scholarly exterior turns out to be misleading and suitably loosened up by some beer they turn out to be a bunch of good lads. There is great excitement one night, after a particularly rare Pipit has been sighted close to the pub and the birding lads eagerly tell us about it. We also check out the climbing log book that is kept behind the bar and turn the pages of stories of epics, genuine thrills and sometimes real wit and humour.

Someone has written in large letters: "Gary Gibson is the biggest disaster in the history of British climbing." We mull on this awhile and agree that while Gary has his critics, this is somewhat harsh to say the least. Most regular climbers owe Gary considerable gratitude for his extensive efforts over the years.

Once the chat (read bullshitting) gets fully underway, we invariably drink at least two pints more than we should as old geezers in our fifties and soon it is time to leave. We stumble out of the pub and into the (often) pitch black Lundy night to make the walk back over the fields to the doss. If there is no cloud, the stars and the moon are sometimes fantastically clear despite the loom of light on the horizon from Devon and from the Swansea area. Other nights, visibility is nil and the westerlies drive the rain in almost horizontally as you struggle up the hill, over the stile and hurry to the cottage to get a late brew on.

The night sky on Lundy is counter pointed by the often wonderful morning light there. Because the island is so small, the sunlight strikes the sea all around it and the vibrancy of the light is sometimes quite startling. I once discussed with Jim Perrin the respective merits and sense of place of both Snowdonia and the Lake District. We agreed that while the Lakes are truly beautiful, Snowdonia has the extra factor of mystery and to my mind Lundy shares that dark Celtic quality. It is not difficult to imagine pirates and other outlaws there, and despite its now generally peaceful character the island has a violent history. I can easily imagine there to be ghosts there and in the depths of the night (when the electricity goes off) the place can easily seem isolated and primitive. These thoughts though are easily offset by a bright morning and the prospect of some of the finest granite climbing in the British Isles.

And now another Lundy trip is drawing to a close and Mick and I are walking down past Millcombe House and through the trees towards the island's landing stage to board the Oldenburg to sail back to the mainland. We are somewhat apprehensive, as the sailing time has been brought forward two hours due to a force seven gale rushing in from the west. It is thought that if we do not sail this afternoon, we may not get off the island for a couple of days. Neither Mick nor I are remotely good sailors, so a full English breakfast and a couple of pints have been taken on board---at least we'll have had something to chuck up! In fact, the trip back to the dry land of north Devon is considerably worse than we expected, with enormous seas that made it hard to credit that we were in fact within the Bristol Channel.

It is by far our worst ever Lundy crossing and the scene on the Oldenburg is one of Olympic level puking. I escape this unpleasantness (only just) but poor Mick suffered a grim journey. At one point, the boat is followed for about thirty minutes by an RAF Sea King helicopter and we wonder what they know that we don't! At long last, we make it back to the fleshpots of Bideford and are glad to once again be on dry land. We load the gear into the car and head north up the M5. Four hours later and we're supping pints in a Derby pub and reflecting upon a good trip with the full variety of the Lundy experience. The island is a unique place and in the right weather a rock climber's paradise. It is one of the great climbing adventures in Britain and if you haven't been I urge you to make the trip. Believe me the mystery of Lundy will call you back.

Diamond Solitaire:Original Photo: Ken Latham

Steve Dean 2012