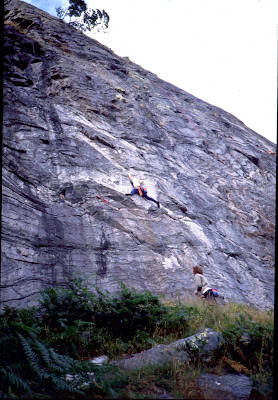

Simon Stewart climbing in Glen Clova;Image-Simon Stewart

A’Chreag Dhearg. Climbing Stories of the Angus Glens. Compiled by Grant Farquhar.376 pages, paperback, drawn on cover, perfect bound. Scottish Mountaineering Press. £20. Ilustrated throughout by black/white, colour photographs.

‘They shattered the spell of the mighty Dr Bell, they were all good men and true’

From a song by Tom Patey

When I lived in Scotland in the 1960’s the southern aspect of the Cairngorm massif was hardly known to my Edinburgh companions of the Squirrel’s. Although I used to go to Dundee regularly on business, climbing on the Arbroath sea cliffs on occasion en route, I had not then heard of the climbing revolution that was under away in the Angus Glens. I stayed in nearby Broughty Ferrry where the big attraction was the Folk Club, highlighting Ewan MacColl (I was to learn later that he was from Salford where he was known as Jimmy Millar). So this book, compiled by Grant Farquhar is revelatory and was a joy to read by this old timer.

The first articles in this compilation illustrate the story of the area, that Dundee used to be the centre of the manufacturing of Jute, and that in the First World War, its denizens were very much the recruiting City of the Black Watch regiment, which suffered many number of deaths and injury. We also learn a little of the family history of the compiler of this volume, a local boy; a Dundonian who now resides in the Bahamas but who has a track record of difficult ascents around the UK, and an equally impressive CV as a climbing writer.

Also surprisingly related in this book, there was one of the first access battles, when the regular route, through all the way to Ballater and Braemer from Forfar (the name by which the whole Angus region is known) was blocked by the Landowner. This ended in the Court in Edinburgh, and the claimants won one of the most important cases, in the history of the outdoor movement. This known as the battle for Jock’s Road, so well recounted by Des Hannigan, a local climber who made his name further south on the Cornish sea cliffs. In January 1959 occurred a terrible tragedy following the route from Braemar, along the Jock’s road to Forfar, a distance over 18 miles, and which goes over the 3,000 foot contour. The party of five became lost in worsening conditions and eventually perished; there was wide publicity at that time and led to the present day mountain rescue in the district.

The early mountaineering in the area was at the initiative of the SMC, meets were held at the home of Hugh Munro (a baronet no less) whose family seat was near Kirriemuir, whose name is now so aligned with his list of peaks in Scotland over 3000 feet, published in that clubs journal in 1891.There is a photograph in the book of a five strong party roped together, in winter conditions on the Forfar hills. Whatever global warming is affecting our winters now, in the latter years of the 19th century, the snow and ice could be counted on by these stalwarts. Another famous figure who lived close by was J M Barrie author of the Peter Pan stories, although he was not a climber, inevitably quotes from his work appear with some regularity within this book.

Simon Stewart belaying Grant Farquhar on 'The Fuerer'- E4-5c, Craig Dubh: Photo Graham Ettle

One of the outstanding pioneers to emerge from this area was JHB Bell, who pioneered some of the great climbs on Ben Nevis, besides local classics in the Angus Glens like Maud Buttress. He was also a writer of some distinction. I can remember how his book, ‘Bell’s Scottish Climbs’ published by Gollancz was well received when it appeared in 1988.

And so the scene is set for what must have been one of the most action packed groups to emerge from a big City to find their way into climbing, winter and summer. A group of teenagers, none who had been on any kind of course, who came into the sport a traditional way, learning by their mistakes, but from the first keen to explore, to new route, but most of all to enjoy themselves and find out what the boundaries were to their lives. They came together and tongue in cheek, called themselves; ‘The Men of Steel’, and many appear in the mss as only their nick names; Dr Evil (Grant), Pot, Hendo etc. One without a nick name but one of the keenest new routers was Simon Stewart. In his writings he claims that he was never the best climber of the group but his new routes on the cliffs of Glen Cova bear a witness to his abilities at that time.

They based themselves in the Carn Dearg Mountaineering Club hut in Glen Clova, and they also became regulars at the pub in that valley. This was in the mid 1980’s, and illustrates how much climbing is now changed with the popularity of indoor walls, diets, training, fitter, stronger, faster. At a later date some of the Men of Steel found places in Dundee; buildings they could climb on notably the walls of the Engineering Department of the University, but they were probably amongst the last groups to find out what climbing was all about by themselves?

We are brought up short by the chapter on the ‘Life of Reilly’, this tells of the story of the twins Ged and Ian Reilly. By this date some of the Angus climbers were travelling further afield. 21st January 1978 Ian Reilly and 19 year old Brian Simpson fell from off a route in the inner corrie of Creag Meagaidh. Ged who was in the area on that day went looking for his brother. By the time they were found it was too late, and both had succumbed to their injuries and the cold. Ged despite this terrible accident still climbs.

In a book of such length there is only space to concentrate on articles that give the feeling of the work, so I will only highlight the ones which I think were typical of the whole.

The first is by Grant Farquhar himself and is titled ‘The Pale Rider’ and goes out on a limb deciding how dangerous climbing really is? This thoughtful article had its genesis, in an e-mail from Simon Stewart. In that he noted that the three most experienced and oldest climbers who he had ever climbed with, Andy Nisbet, Martin Moran and Doug Lang had all died at great ages in climbing accidents. This posited the question do climbers become more at risk as they grow old?

Grant is a psychiatrist so well able to pontificate on risk taking, and he comes to the conclusion that climbing is not as dangerous as some would believe, and for instance other activities like Base Jumping are much so. As someone who gave some lectures on this subject I would say that there are now different levels of risk involved in the activities. Sport climbing should be safe, trad rock climbing less so, winter climbing even more so, with the most dangerous being greater range mountaineering with Himalayan the most demanding in this respect. Freud inevitably is included in Farquhar’s musings, with both, Libido, the sex drive and Thanatos the death wish mentioned. His conclusion that we are all going to die in any case is true and though most of us try to avoid facing up to this, his advice is to enjoy our lives and to get out climbing.

This leads on to the terrible accident on Creag Dubh, under the title Redemption on Creag Death which befell Simon Stewart in the early part of 1987. Pushing his grades he set out on a route on the main wall, Acapulco a badly protected E4. When I lived in Edinburgh it was a favourite haunt of the Squirrels. Bugs McKeith and I even soloed the frozen water course which splits the crag one winter, and with Dave Bathgate I made one or two first ascents. It is a difficult cliff protection wise and unfortunately when Stewart fell off Acapulco what gear he had pulled and he hit the ground and was badly injured. Fortunately a mountain rescue team were training nearby and he was lifted by chopper to Raigmore Hospital in Inverness, somewhere that has poignant memories for me for it was where I first met my future wife, who on her way to ski in the Cairngorms was involved in a road accident. It was to be thirty years before Simon climbed again. The accident had the outcome that he concentrated on his University studies, and much to the surprise of his lecturers he became an outstanding student which led him to eventually become a Professor. Much of his early climbing and first ascents was with fellow female student, CAMS. In 1992 his reverie was to be interrupted by a ‘phone call from fellow Men of Steel member, Graeme Ettle informing him that CAMS, Cathy had died in the Himalaya.

The final article I would like to highlight from this book is by Sophie Grace Chappell on the naming of climbs. Many climbers have previously used this has a theme for such, but Sophie has an unusual take on this with the titles of many pop and wider musical pieces, even old music hall favourites. How climbs are named is often the source of much discussion, usually it is up to those making the first ascent to do this, but in the case of Glen Clova it is revealed in this book that many of the new routes are named in keeping with already existing challenges.

Andy Nisbet in his natural environment

The book almost finishes with a poem by Sophie in memoriam to Andy Nisbet and Steve Perry, two leading Scottish mountaineers who died on Ben Hope in February 2019, and ends with a list of the sources from where some of the articles originate. The work involved in putting together such a compilation is impressive and Grant Farquhar is to be complimented on that. All profits from this are to go to the Scottish Mountaineering Trust, a Scottish charity whose task is to make grants to organisations that promote recreation, knowledge and safety on the mountains, especially the mountains of Scotland.

Dennis Gray: 2022