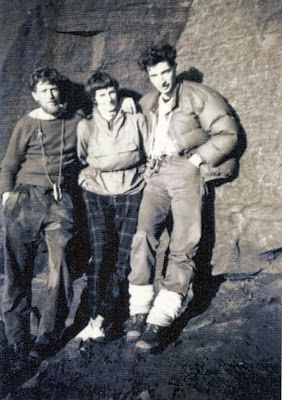

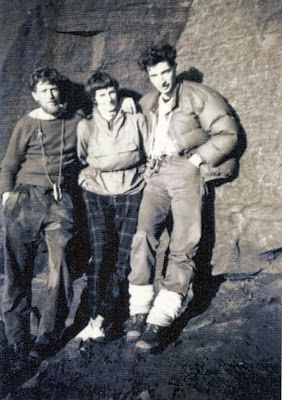

The Drasdo Brothers- Neville (left) and Harold outside Lakeland's Old Dungeon Ghyll at one of the last Bradford Lads reunions they attended together.

‘Derision

is the burden that the avant-garde learns to bear; but in 1947

climbing had an oral culture, remarkable for the start of the post

war ascendancy of northern working class British climbers’ Harold

Drasdo

Imagine

you are 14 years old, you have been climbing for three years since

1947 and in the winter of 1949/1950- March to be precise- you meet in

the Hangingstones Quarry at Ilkley, a 20 year old from Bradford, just

returned from Athens, on National Service. Tall and gangling, he is

however so knowledgeable about climbing and climbers, as you begin to

realise whilst chatting in a corner attempting to stay out of the

biting cold wind, ever present on Ilkley Moor in winter. You hang on

his every word. You complain about the weather and the cold, but your

new found friend declares he has 'been dreaming about being here in

these conditions for the last two years' whilst soldiering in Greece, where 'the heat had been unrelenting’.

There

were no other climbers present that day, it being mid-week (the

average worker was still employed six days a week in March 1950). I

had bunked off school and my new found friend was on demob leave, so

we agreed to climb together. Our first route being the ‘Fairy

Steps’ a Hard Very Difficult, which was climbed in boots, followed

by ‘Nailbite’ another Very Difficult , and finishing with

‘Josephine’ a Severe wearing rubbers. It is hard for me now so

many years later to wonder what I must have been like as a 14 year

old, but my partner that day wrote later I was a ‘streetwise

youth’. As we departed to head home he to walk over the moor to

Dick Hudson’s to catch a bus to Bradford, me descending to Ben

Rhydding for a bus to Leeds I learnt that he was Harold Drasdo, soon

to be known in local climbing circles as ‘Dras’.

'Dras' when he was working at Derbyshire's White Hall Outdoor Centre

Drasdo

is an unusual name (there is a town by that name in Germany south of

Berlin) , and so it stuck with me, and over the ensuing weeks meeting

at Ilkley and other West Yorkshire outcrops, and coalescing into a

larger group of activists, we became known as 'The Bradford Lads'.

Several of whom besides the Drasdo’s; such as Pete Greenwood, Don

Hopkin and Alf Beanland, were also to develop amongst the lead

climbers of our area, and later until his death in the Alps in 1953,

our best known group member was Arthur Dolphin. Nobody of my age was

to my knowledge climbing regularly in that era, unlike today with the

spread of indoor climbing, but in 1950 the popular image of climbing

being it was highly dangerous, and in retrospect it actually was.

One

element now revolutionised was the basic equipment then in use,

another was a lack of instruction, for the only pool of knowledge was

held by its regular participants and you learnt on the rock by

example or experience as you progressed. And also perhaps you might

have managed to obtain a copy of the then recently published Penguin

paper back, ‘Climbing in Britain’ by John Barford for the

princely sum of one shilling (ten pence). And before the modern

reader thinks that was an incredible cheap bargain, Dras told me at

his first job as a 16 year old he was paid £1 a week. But he did

enjoy two weeks holiday, which made him feel lucky to be so employed!

Petrol

rationing finished in 1950 and we discovered hitch hiking. And so

after having perforce needed to concentrate on our local outcrops, we

began to travel far and wide with the Lake District and Langdale in

particular being our Mecca. We stayed in barns and the one at Wall

End Farm in Langdale became known the length and breadth of Britain.

Often I was in the company of Dras and eventually I met his younger

brother Neville. They both made major contributions to climbing,

together and individually but for me it was my thinking, my education

they affected most. Like me they were both scholarship Grammar School

boys, leaving at 16 years of age, and working at low paid jobs, Dras

as a clerk in a Health Unit and Neville an opticians; but studying at

night school and eventually gaining entry into Higher Education,

their outstanding later careers being founded on an impressive

ability to master facts.

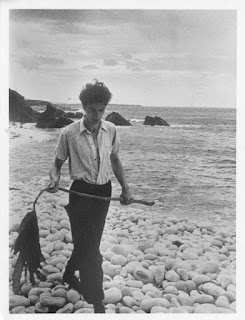

Cairngorms 1958.

Dras was reading widely from the first, and

I can remember him as we spent long winter nights in a doss under

Castle Rock, in Thirlmere recounting to me the story of the first

ascents of the North Face of the Eiger, and the North Face of the

Grandes Jorasses. I was so smitten by these stories, I sent to Paris

for Anderl Heckmair’s ‘Les Trois Derniers Probleme Des Alpes’.

Which despite five years of French at school I struggled with to make

sense of the stories, but Dras was reading much wider than

mountaineering books, and we began to think of him as an

intellectual! I can also remember him recounting stories to me about

hitch hiking, and one article in particular he valued highly, was

written by the American poet and mountaineer Gary Snyder.

Through

such sharing I found out that Dras, like me, had started climbing at

Ilkley in 1947. Why Ilkley? If you lived in Bradford or Leeds, and

relied on public transport, then it was easiest to reach at a time

when the dislocation caused by the war was still a major factor in

our everyday lives; food, clothes, and fuel were all still rationed.

To visit Almscliff was much more difficult than Ilkley. For me it

meant a bus to Bramhope then tramp the miles from there to reach the

Crag. Despite such difficulties there was a keen spirit of adventure

in our approach which was essentially light hearted. Being so much

younger than my companions I was sometimes the butt of their humour,

one such instance was when they contacted The Bradford Telegraph and

Argus and joined me as a member into their ‘Nig Nog club'! It

seems incredible now that this could have existed in a City with a

high ethnic population, but this was a young person’s club

sponsored by that newspaper.

I read out my ‘joining’ letter to my

older companions the weekend after receiving this by post in Leeds 6.

‘Dear Dennis, we welcome you as a ‘Nig Nog’ into our club,

please try and make all your friends ‘Nig Nog’s’ as well’.

They laughed long and hard at this, but I got my own back. We lived

next to a chemist and I managed to obtain some medicine bottles, and

labels. I poured some coloured liquid into these and handed one to

Alf Beanland, Dras, Greenwood & Co. On the label I had printed, ‘Peter

Pan Liquid Jollop for Ageing Youths’ I

think in those early years of our friendship two climbs stand out. In

September 1952 with Dras in the lead, we managed to pioneer one of

the Lake District’s hardest climbs of that era ‘The North Crag

Eliminate’ at Castle Rock; which is still graded Extremely Severe.

This was in retrospect an unusual climb, for one of its pitches meant

climbing a large yew tree, then from its top most branches launching

onto the rock face to make a difficult upward rightward traverse to

reach a secure ledge, below the intimidating top pitch.

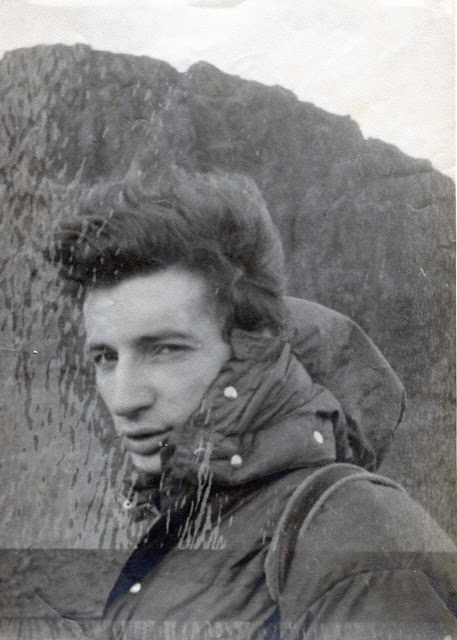

Castlenaze 1957

For me, being

at that date a small 16 years old, it was the moves from off the tree

I found the most difficult of the route. This climb illustrated for

me that whilst Dras was not the most naturally gifted performer in

our group- Greenwood and Dolphin being more so- he was the most

determined, and once he set his mind to a task he was usually

successful.

Another

memorable day in 1952 was when Dras and I climbed Hangover on Dove

Crag, and noticing on a buttress to its left hand side, an impressive

line, which commenced with a steep crack. Dras set off up this, but

it was seeping wet inside its edges, and some way up this he managed

to hang a sling and I lowered him down. I then tried to lead this,

but could not reach as far as Dras and hanging by the sling he had

placed I could see that the next moves would be beyond me, so I too

then baled-out. The Following weekend I met Joe Brown in Langdale,

and I told him about the outstanding difficult line we had discovered

on Dove Crag.

He was very interested, and with Don Whillans visited

and ascended the route which they called Dove Dale Grooves. A route

so difficult for its era, that a decade elapsed before it was

repeated. The reader may be surprised, but Dras was not annoyed with

me about blabbing about our great find to Joe, for we both recognised

that if any climbers could have pioneered the route at that time,

probably only Brown and Whillans were capable of achieving such a

result.

The

death of Dolphin and the opportunities that developed for some in the

1950s for entry into higher education, or to better ones prospects in

work further afield would eventually lead to a break-up of The

Bradford Lads. Dras managed to study in Nottingham and qualify as a

teacher. This then led to a career in Outdoor Education, first in

Derbyshire at Whitehall, but then as the Warden of the Towers

Education Centre near to Capel Curig . But throughout he continued to

explore and pioneer new rock climbs. A major development, in which he

and his brother Neville were key figures, was the discoveries they

made over several visits to The Poisoned Glen in Donegal. This came

about by Neville exploring climbing possibilities in that part of

Ireland in 1953, returning home and convincing Dras about possible

new routes that might be found in that valley, which they visited in

1954. Over many visits in following years they did manage to climb 20

new routes, perhaps the two which have become best identified with

them being The Berserker Wall and the Direct on Bearnas Buttress?

Donegal Days

With

his outstanding literary abilities Dras was invited by the FRCC to

edit their first ever guidebook to the Eastern Crags, an area in

which he had been an original pioneer with classic routes like

‘Grendel’ (VS 4b) in Deepdale. The volume he produced in 1957 was

a ‘big effort’ on his part, for without transport and often minus

a climbing partner, much of his checking and routing was achieved

solo, and taking these problems into account, the guidebook he

produced was first class. Transport was a big problem in our early

climbing days, for as the 1950’s progressed hitch hiking became too

slow and crowded (so many other competitor’s out on the road also

seeking lifts) and therefore many climbers moved onto motor bikes.

Dras

was one of these, but initially he did not display great driving

skill. He bought an ex War Department machine, for I believe about

£40, and drove it up to Langdale. With me riding pillion we set off

from the Old Dungeon Ghyll Car Park to ride up to Wall End Barn, with

our fellow Bradford Lads cheering our departure. At the first sharp

bend leading up to our destination he lost control, wobbled across

the road and hit a wall. I was lucky and landed on a grass verge, but

Dras was injured, fracturing an arm quite badly. So it heralded for

us a return to hitch hiking.

In

1971 Dras edited a new edition of the Lliwedd guide for the Climbers’

Club having been elected to that organisation in 1966. Taking this

on, was truly a brave decision for despite its huge bulk and ease of

access it was seen even at that date as something of a backwater,

whereas once in the early years of the 20th

century it was at the cutting edge of climbing development in this

country. Maybe it might yet be again, but Dras had to overcome the

curse of Lliwedd in preparing this volume, for its two previous

editors, Archer Thompson in 1909, and Menlove Edwards in 1936 both

ended their lives, committing suicide by poisoning. He remains

however the only such guidebook editor to have published such a

volume in both The Lake District and Snowdonia.

Latter days: HD on the esoteric Tremadog VS 'Wanda',where a basking adder held up progress!

Established

in Wales and a key figure in the development of Outdoor Education,

Dras decided to put his thoughts about this into print and he

produced a seminal work, ‘Education and the Mountain Centres’.

This was a thoughtful analysis of the role of risk and the experience

of an exposure to nature in the development of young minds; in 1972

when it was first published it made a major impact on this then fast

developing field of education. It remained in print for many years

and sold hundreds of copies nationwide. A more eclectic work that

Dras was involved with in this decade was a joint publication with

the US climber and academic Michael Tobias, ‘The Mountain Spirit’

published in 1980. This was in retrospect an unusual and surprising

work, a potpourri of articles, poems, and anthology, and some pieces

written especially for the book by David Roberts and Arne Naess and

by the authors. It was full of Zen and Tao, including a piece by HSU

who visited every mountain range in eastern China in the 16th

century. It was met with such a mixture of like and dislike that it

remains one of the most unusual books to be published in that era.

A

person who was impressed by ‘The Mountain Spirit’ however was a

friend in Manchester, who at that date was a drama student, Nick

Shearman. I attended at a theatre in town to see him act in a stage

adaptation of the Dracula story. He was also a keen rock climber, and

thus when he admitted an interest in meeting Dras I took Nick to meet

him at The Towers. Shearman was an enthusiast for the plays of Samuel

Beckett, and once met up they gelled and discussed Yeats, Beckett,

Joyce and mountain themed writing till the wee small hours. Shearman

remained impressed, and I valued his opinion for he was an

outstanding personality himself, who went on to enjoy a major career

in television production as an independent and at the BBC. This

meeting led on to me organising in Manchester a Mountain Literature

Evening, at which Dras was one of the speakers, others being Ivan

Waller telling about an amazing escape from a crashed plane in the

war and Tony Barley who survived an epic rescue after a huge fall in

a remote area of South Africa; the theme of the Evening being ‘Risk

and Adventure’.

Dras was a serious thinker, and he loved to draft,

rewrite either a talk or article to firm up his ideas which is why he

did not publish easily, but the articles he did finalise such as ‘The

Art of Cheating’ originally published in Mountain Magazine are

worth re-reading, again and again.

Bradford Lads at that thar ODG.

In

1997 Dras published an autobiography, ‘The Ordinary Route’, which

besides describing a life full of climbing in many different

locations Yosemite, Greece, The Sinai besides the UK and Ireland he

revealed his thinking about access and conservation in mountain

environments. I had forgotten just what a good read this book really

is, having re-read it before commencing this article, and the chapter

on access campaigns underlines his lifelong belief in anarchism;

which confirms the need to support local action, away from

centralised decision making.

Dras

was a lifer when considering his climbing activities, and in the year

2000, he and his brother Neville celebrated 50 years of new routing;

‘Cravat VS 4C’ on Bowfell’s Neckband crag in 1950 and ‘Two

against nature S 4a’ on Craig Ddu, Moel Siabod in 2000. He was a

consistent explorer of crags in North Wales, and continued to be

active in the Arenig’s for many years, accompanied by John Appleby

and other friends besides occasionally his brother.

Neville

Drasdo has now retired from a stand out career in optical neuro

physiology, as a Professor in the school of optometry and vision

sciences at Cardiff University, producing 80 research items and

receiving over 2000 citations. As a climber, many of his early years

were confined due to working on a Saturday in Bradford. Climbing on

his one day off he nevertheless managed to pioneer some highly

technical routes on local outcrops of which Bald Pate Direct E2 5c at

Ilkley and Alibi HVS 5b at Widdop are illustrations of his abilities.

Physically he was a doppelganger of Dras and when I was 15 and

Neville 19, in 1951 we met up in Glencoe, staying in Cameron’s Barn

high in the Pass on the edge of the Inverness Road. We ascended

several classic routes on the Buachaille Etive Mor; the Whortlebury

Wall, Agag’s Groove, Red Slab and The Crowberry Ridge Direct.

HD on the first ascent of 'Jac Codi Baw' on Arenig Fawr

We

even tried the then hardest route in Glencoe, Gallows Route; Neville

almost succeeded on this but sticking in the final groove, unable to

exit from it, his retreat back down the groove and across the

traverse he had made to reach this was heart stopping! This climb had

been unrepeated since its first ascent by John Cunningham in 1947,

and for us teenagers to nonchalantly be attempting this makes me

wonder at our initiative even now.

Neville went on to make some

impressive first ascents on Skye and in the North West Highlands of

which his 1000 ft route on the Sgurr an Fhidhleir in Coigach was a

major development in that area. And in North Wales his most

impressive new climb was in accompanying Joe Brown on the 1st

ascent of ‘Hardd’ E2 5c on Carreg Hyll Drem.

Dras

died in 2015 and though Neville is now suffering from a serious

medical condition my most recent message from him was that he was

still ‘Hanging On’.

And now as I finish with this, I see in my

mind’s eye two figures standing together in the winter of 1951/2.

We are in Borrowdale early in the morning and snow is lying deep on

the ground and set like iron. This vision is one of the Drasdo

brothers, wearing boots shod with Tricouni nails, and they are just

leaving to climb in the Newland’s Valley. The rest of us Bradford

Lads are heading for Great End, long ice axes at the ready, to do

battle with its famous gully climbs. But that was not for Dras, he

was ahead of the game and he had realised that the future lay in

climbing rock routes in winter conditions. They did just that,

climbing a severe summer route, made all the more demanding layered

by snow and ice.

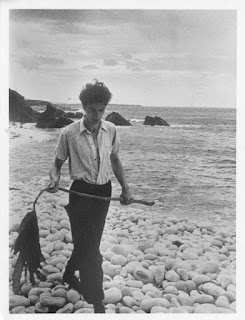

Harold under Pavey Ark

Harold

and Neville Drasdo were two of the most outstanding, creative

climbers of my generation.

From humble beginnings they carved out for

themselves lives and careers of great worth and their achievements

and character will keep their memories alive for all who knew them.

Which in Dras's case are the hundreds of school children who were

introduced to the rivers, hills and moorlands of an outdoor adventure

playground, which is a truly suitable memorial.

Dennis Gray 2018.

Special thanks to Maureen Drasdo and Gordon Mansell for supplying many of these never seen before images.