I conducted this interview for the Leeds University Union Climbing Club Journal of 1973, the editor of which was Bernard Newman.It is fair to say at that date Allan was a (the?) leading pioneer of Yorkshire and Lakeland climbing. Dennis Gray: Do you have any fondness for such interviews? ‘Allan Austin tells all!’ Do you think they serve any useful purpose?

Allan Austin: No I don’t think they serve any useful purpose whatsoever. They merely provide an easy way to collect a load of print for a magazine.

D.G. Much of my early climbing was undertaken with the now legendary ‘Bradford Lads’, who were at the forefront of British climbing in the late 1940’s and early 1950’s. I once made out a ‘family tree’ and was surprised at the links, some tenuous, but some close between that group and most of the leading climbers who followed on over the next decade. I believe your early climbing was done with one of the ‘Lads’ – Mike Dixon?

A.A. No, I used to climb with Brian Evans and Mike was a friend of his. The first time I actually climbed was with Ashley Petts, and the next on a Mountaineering Association beginners-course in Llanberis. This was organised by Robin Collomb-and that would be at Christmas 1955.

D.G. You were very lucky in having Brian Evans as a partner in those early days. In my opinion he was one of the steadiest and most under-rated climbers of his generation. When I first met you in 1956, I thought this guy will, either win fame of end up lame! Your climbing was characterised by strength, determination and drive, which often led you out of your depth!

A.A. There is a fair amount of truth in that! We used to climb as a team of three; we needed the third man to rescue the leader after he had run out of strength. We recruited Doug Verity-a big bloke, who could stretch out his hands flat, so I could stand with all my weight on them! I climbed with Brian because he was of my age group. I had transport and I was keen, and he was a good climber with no transport. Brian’s idea was to climb at Very Severe, and he was the only bloke in the club (The Yorkshire Mountaineering Club), besides Ashley who consistently led at that standard. They were not really hard you know, but with the aid of my transport we had a lot more opportunities, and therefore we became very good as a result.

D.G. So initially you feel that Brian Evans was the driving force of your group?

A.A. Definitely: Brian would say ‘We’ll do this route’ or ‘We’ll try up there’. The first big route we pioneered was Stickle Groove on Pavey Ark. Brian had said to me in the club hut at Ilkley, ‘We’ll go to the Lakes and repeat Dolphin’s climb Chequer Buttress’. It had not then been repeated. And then once there, he noticed a big gap near to this, and so we filled in this gap and also climbed Chequer Buttress.

D.G. In the late 1950’s you pioneered many outcrop climbs, but just like many others before, and since, you used aid which has been shown to be superfluous. I am thinking of climbs at Brimham such as Hatter’s Groove and the first pitch of Minion’s Way where you stood on your second’s shoulders!

A.A. No I didn’t. We had spent a month trying it like that, but in the end we climbed it free.

D.G. Well, that is as maybe, but today you are feared by young climbers who do make similar errors, for you will, and rightly so in my opinion speak out against such mistakes. But is this not a case of ‘the kettle calling the pot black?’

A.A. Everybody makes mistakes, and I think I have fewer pitons per foot climbed of any climber of my own time. Up to 1960 we had pioneered two hundred or so new routes, and I don’t think we used aid on any route on gritstone, except for Hatter’s Groove, and in the Lake District, out of a hundred new climbs-only half a dozen pitons. I am not proud of using these, for I am weak like everyone else; but having said that I will stand back and realise that utilising them was a mistake. I for one do not try to back my ‘blunders’ up.

D.G. Having read the recently published, Fell and Rock New Climbs booklet, I was surprised at the amount of aid the new generation of pioneers are allowing themselves to use in the Lake District. Do you think that some climbs are being forced today that should be left until standards rise further in order that they can be climbed without such methods?

A.A. Oh, hell aye! The prime example of this is Peccadillo. This had been tried by-Geoff Oliver, Les Brown, and several other outstanding, leaders; and they had all failed to solve this problem. But along comes a modern team, who also could not climb this route, and so they abseiled down and fixed an in situ sling, which they then used to get them over the difficult section.

I reckon this sling, marks the point at which they failed, and it has solved nothing. It was not a legitimate ascent and it should not be recognised. Climbers now seem to be picking a line up a cliff and using just enough aid to make sure they are successful in climbing it, without really considering if the climb would be possible without this. I am not in a position anymore to change things. Once I might have climbed such routes without resorting to aid, but I cannot anymore. Shouting is not enough; it really needs some very good climbers to be active in the Lake District again. An example needs to be set. If three or four of the areas leading climbers are using a lot of aid then other people are bound to follow their example.

D.G. Don’t you think in some of these cases a stronger line should be take by the Guidebook editors?

A.A. Yes I do. In the new Langdale guide, I have been fairly courageous and have cut out three routes, which had utilised excessive aid. If the artificial section of a climb is the main part, then we have not included it. For example-The Pod on Pavey Ark, that was ascended by John Barraclough, using seven pitons for aid. It has subsequently been repeated using only two. In general there is too much of a rush to climb a new route and then get it into print. This is a very bad thing for the sport.

D.G. Do you think the magazines, are to blame for this?

A.A. In part, the system of first ascent lists at the back of a guidebook is also to blame. I much prefer Dolphin’s system of a paragraph about each crag, picking out the historical highlights.

D.G. I can’t say that I agree with you there. You mentioned Dolphin; you never knew him but you have repeated many of his hardest climbs. In the early 1950’s there was nonsense abroad about Joe Brown having created a ‘new standard’ in rock climbing, a ‘breakthrough’. But I believe that Dolphin had already achieved this on outcrops, as also had Peter Harding before Brown and Whillans.

A.A. You are right, but it was only for a short period. When Joe started pioneering his new routes in Wales, Dolphin’s routes in the Lake District were of the same standard. But by 1953 Brown’s routes such as Surplomb and Black Cleft were of a new grade, but not his earlier climbs such as Cenotaph Corner and Hangover, which were only as hard as routes like ‘Do Not’ in Langdale.

D.G. Dolphin was improving every year though, and for example he had climbed a long way up Delphinus and examined many new possibilities on the East Buttress of Scafell before his death. But returning to your early career, you were amongst the first to try to prick the ‘Rock and Ice’ ‘Bubble’. I do remember your article, ‘The White Rose on Gritstone!’

A.A. Ken Wilson, the editor of Mountain Magazine, described it as one of the most biased articles he had ever read!

D.G. You were a little carried away in your attempt to break down the myths. I can remember you standing on Joe Brown’s shoulders when you got into trouble on the ‘Dead Bay Crack!’ This attitude did tend to grind a little with we Rock and Ice members after witnessing such a performance.

A.A. Well, Joe Brown had pointed Mortimer Smith and myself at this climb and then sat back and watched whilst we failed on it. He had to rescue both of us from the crux but I was the one who led it in the end. It took me four hours!

D.G. I led this climb a short while later and found it reasonable. Was it that you were psychologically embezzled?

A.A. No, it was the fact that it was at the limit of my climbing ability at that date (1956). The same day Mortimer and I had failed on Peapod.

D.G. Do you accept though, that some of your statements in that article were a little outrageous?

A.A. The article was written to be provocative. I decided years ago that if you were not opinionated in an article, then it was not worth reading, so I deliberately intended to annoy the reader. It seems I did not succeed in this, but I certainly did provoke some people! To be honest though; at that date there was no one to approach the Rock and Ice on gritstone. There were odd climbers like Pete Biven, Pete Hassell and myself who were trying their easier routes, but the climbs that they considered hard such as The Right Eliminate, we did not even look at. It took us a full year or more to catch up, and to develop the necessary techniques and standards, but in 1956, we were lucky if we managed to climb any of Joe Brown’s or Don Whillan’s routes!

D.G. It seems to me now looking back over these years, that contemporary climbing historians have a wrong view of events in Wales towards the end of this decade of the 1950’s. A recently published book has it that in North Wales in 1957, only one climber not a member of The Rock and Ice Club was climbing the hard, major Cloggy routes. I am sure you will recall Metcalf repeating some of these big climbs in 1956, and you yourself were making early repeats in 1957. Why do you think these reports are so inaccurate?

A.A. Because they were so parochial, I can remember John Disley telling me that when you had four climbers, leading Very Severes, in the Llanberis Pass, that they represented the climbing strength of Britain. This did not include people like Dolphin and his friends active in the Lake District, or the Creagh Dhu in Scotland who were actually climbing at a much higher standard than Very Severe. He could not see past Harding, Moulam, Lawton and himself. This attitude ran on into the late 1950’s when archivists like Rodney Wilson had prepared lists which included the first five or sixth ascents of routes like Cenotaph Corner. He’d never heard of Metcalf or Pete Greenwood! Rodney once informed me that I had done the second ascent of the Black Wall, but I already knew that John Ramsden had also repeated it four years earlier.

D.G. Why do you think you have always concentrated on rock climbing? You have visited the Alps, but you now seem to confine your activities to West Yorkshire and the Lake District. Why is this?

A.A. My holidays have always been short, a fortnight at the most, and working on a Saturday morning meant that I had to get time off to travel to Wales. Hence nearer climbing areas were of necessity my goal. One holiday I took in the Alps it rained and snowed for two weeks and I did not get up a single route. So we travelled on to the Dolomites, where a break in the weather would also because of that mean there would be no climbing for several days.

At one time however, it did seem that we concentrated and only climbed in the Lake District. But for a five year period before that we alternated weekends between there and Wales, and in fact I had managed all but two of the routes in Don Roscoe’s guide to the Llanberis Pass.

D.G. You never managed many new routes in Wales, but you were always out in the front as a pioneer in the Lake District.

A.A. I thought that the Lake District needed a spur to bring it up to the standard of Welsh climbing, and so I was prepared to sacrifice myself for that cause. We only travelled down to Wales to attempt Joe Brown’s routes. It seemed to me then, that there were bigger and harder routes in Wales, and so we concentrated on the Lake District to try to develop the same there. At that date, 1959, there were ten extreme climbs in Wales for every single one in the Lakes.

D.G. Did you manage to carry this policy out?

A.A. Yes, we pioneered some hard climbs but none as big as the famous Welsh routes. Unfortunately we never found any ‘Cloggy’s’.

All we discovered were climbs like those in the Llanberis Pass, so all the major classics in Wales are unmatched in the Lake District.

There cannot be a dozen climbs in the Lakes, which compare to the top 60 in Wales.

D.G. Can you still do one arm, pull-ups?

A.A. No. I could only ever do those at all on the door of the Ilkley hut, which was at such a height that I could start with my arm slightly bent.

D.G In the last few years there has been a tremendous increase in the use of indoor climbing walls. I have visited the Leeds University wall in the past and last year I became a regular visitor, but this year it bores me. Perhaps it is because I cannot compete against the youths one now finds there, climbers like John Syrett, John Stainforth, and that, long-haired yob Bernard Newman! The last time I saw you there, you were not exactly ‘number one.’ Do you mind being burnt off by the younger generation, or will you keep on going until you draw your old age pension?

A.A. No I do not mind them burning me off. I go to the wall mainly for the social side, to meet other climbers: they are not such a bad lot- really. I went there once on my own and spent twenty minutes before going home because I was bored. It is the people who go there, which make the wall an interesting venue, but it also might be the competitive element as well.

D.G. Climbing in this country is very parochial and I think West Yorkshire climbers are as guilty of this as any, including the Scots. Why do you think these attitudes exist- Lakes versus Wales, Yorkshire versus Derbyshire?

A.A. It is just nationalism I suppose. Everyone likes to believe that they come from a special area. When I first started climbing I did not care two hoots whether it was the Lakes or Wales, that was until I met Joe Brown. His remarks about Yorkshire and the Lakes tended to get my back up, and I guess it all stemmed from that.

D.G. Do you think that was a deliberate tactic on his part?

A.A. Oh, hell aye! Joe has spent his life knocking others; he never stops doing this. One-upmanship is Joe’s life.

D.G Do you think this is because Brown has a superiority complex?

A.A. No, I think he just likes to set people up. It is his form of humour. He hasn’t got a superiority complex and he is not an inverted snob like some of the other members of the Rock and Ice. A typical remark to me after I had failed on a route would be: ‘I always said you were the best climber to come out of Yorkshire, but really there never much good are they?’

D.G Of all the routes which you have pioneered, which gave you the most pleasure and which do you think was the hardest to complete?

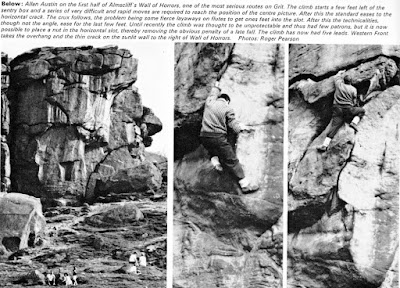

A.A. The Wall of Horrors gave me the most pleasure. It had been a long-standing problem and the scene of many previous attempts. Climbing a route with such a long history is always satisfying, even more so than discovering a new line. I had been trying it for a couple of years. Nowadays one might resort to using aid, a peg or a sling, in case someone else came along and bagged it before you.

D.G. I remember Dolphin telling me as a boy, of his top-roped ascent of the Wall of Horrors. And he had decided to leave it to be led on sight by the next generation. He sensed that there was a change in climbing ethics, and considered that on-sight leads should be encouraged for first ascents. I personally was upset when you continually top-roped the route prior to leading it. I think it would have been better if you had led it on-sight. Do you still think that you were justified in your methods when Dolphin had already shown it was feasible?

John Syrett on Allan Austin's 'Wall of Horrors'

A.A. A top rope ascent does not show that the route is possible, and anyway in that era most of the hardest gritstone routes had been top rope inspected before their first ascent. I once saw John Gosling leading a new route at the Roaches in Staffordshire. He was able to clip into a piton, which had been pre-placed on an abseil rope without even looking for it. He made the route look easy! I agree that sight leading is the most satisfying way to climb, but on outcrops where standards have always been pushed, I do not think that top-roping will ever be abandoned.

D.G. You have climbed at Harrison’s Rocks in Kent, do you think that the routes there should be led as a matter of course, instead of being top-roped.

A.A. Yes, climbing at Harrison’s should employ the same technique as any other outcrop, for example Almscliff. The rock is generally quite sound enough.

D.G. Several of your friends have been killed whilst climbing. Do you think that such is worth the sacrifice?

A.A. Climbing is not worth getting killed for, but without some spur you just would not try. The reward in climbing is the intense personal satisfaction of having overcome a challenge with a certain level of danger involved. Without that danger there would be no point in going climbing, you might just as well be in a gymnasium or on a climbing wall! The only reason you go out onto a mountain is because it is such an unfriendly place, and you overcome the difficulties. Nowadays we make up a lot of rules, put them into a straight jacket, and call them climbs.

D.G. I have found that one, of the best aspects of climbing is the Friendships that you might make.

A.A. If you climb a lot you meet other people who climb a lot and who have the same attitudes as you. Under stress, even if it is voluntarily induced, you find a lot out about people and if what you discover is good, then they, become a friend.

D.G. Do you reckon this is why women have not so far fitted into climbing circles, because they are not in a position to strike up these kind of friendships?

A.A. Basically I think women are motivated differently, for they have no need to try. Man’s role has always in the past been the breadwinner, and up until recently women have never been in a competitive situation. I cannot think of another reason why women are not interested in climbing; they are only interested in the blokes, not even in the other women. The proportion of women who climb for ‘climbing’s sake’ is small.

D.G What is your opinion of solo climbing? I refer to the sight soloing of hard routes, because your maxim has been, ‘sane men only lead on sight where there is some protection’.

A.A. I would like to be able to solo, really hard routes. If it gives a climber a kick to solo a climb, then I have nothing against it, because we go to the mountains basically to enjoy ourselves.

D.G. Who-do you think has been the most outstanding climber of your aquaintence?

A.A. The most impressive climbers I have ever climbed with were Joe Brown, Pat Walsh and Don Whillans. Of them all, I think Whillans impressed me the most. I could not understand how Joe climbed, but Whillans climbed like myself only better. I do not know what made Walsh climb, but he also climbed better than-me, although he did not have any sense of dedication as far as I could see. He did not seem to have any drive, his techniques were not marshalled, he-just walked up to the foot of a rock face and ascended it. Whillans climbed just like I did, he thought about a route and arranged protection like I did, only better. Joe’s style was completely different; he never climbed like anyone else I have ever seen. He had a style all of his own and I could not assess how he achieved this.

D.G. I think this was the basis of Joe’s ability to psychologically embezzle the people he climbed with. Moseley failed to follow him on the first ascent of the Boulder, which Ron himself was capable of leading quite easily.

A.A. True, Brown broke almost all the men he climbed with as regular partners. When you think of how good they were when they first started climbing with Joe, they were almost without exception climbing worse when he stopped climbing with them. The only climber who did not was Whillans, presumably he was good at the beginning of their partnership, and he ‘grew up’ with Brown.

D.G. To switch to a lighter tone, the subject of climbing names has always fascinated me. It has been a social commentary almost on the development of our sport. I think you have been one of the climbers who has continually managed to produce excellent names. I am thinking of such as the ‘Ragman’s Trumpet’ and ‘Man of Straw’. How do you keep coming up with names like that?

A.A. Well, generally I am told by other climbers that my names are poor. The people who climb with me generally title the routes; they do not accept my names.

D.G. So someone else deserves all the credit?

A.A. Ragman’s Trumpet was a particular line on Bowfell. The Tomlin team rolled up one day and they declared, ‘We will climb that one day, by God, and we’ll call it the Ragman’s Trumpet!’ They were getting at me I suppose. The Man of Straw was myself; I just did not like placing that peg. I have done the route since without it and there is not much difference in standard.

D.G. Mass circulation climbing magazines are here to stay, and their Circulation’s continue to rise. In my opinion you are no mean writer, some of your articles over the years must be amongst the finest to appear in climbing journals. Why is that you have never contributed to any of the mass circulation climbing magazines?

A.A. The effect that these magazines have on climbing is a bad one. They foster the desire to get into print to the detriment of the sport. For example, if you cannot get up a climb then overcome this by using a piton for aid because you do not get your name into the magazines by failing. The other thing is that it takes me so much effort to write an article, I would rather it went into a journal, where it is kept historically, than a magazine which is thrown away! As for the money they offer, which is not much, I might just as well offer my articles to club journals. I am not interested in forwarding the interests of these magazines; any contribution I can give to climbing is free. The only proviso is that I direct where the article goes-and it must not go to these periodicals.

D.G. I must disagree, for I feel that a good climbing magazine can fill a very useful purpose. Getting back to your climbing, do you consider that your hard routes of today compare with the climbs you were pioneering ten or fifteen years ago? Or do you feel that you reached your peak with climbs like High Street and Astra and although your new routes now might be harder, it’s just the fact that you have become more cunning?

A.A. Modern protection methods enable me to still climb at a high standard. If 1972 were 1955 I would have by now, given up all thoughts of hard new routing. Dolphin thought he was at his peak at 27 and I agree with him. I do not think that a climber can climb past his youthful enthusiasm without good protection on routes. It is guts and stupidity, which makes a climber lead, hard bold routes- and you, can only do that when you are under 30. It’s not a question of being married with a family; it is just that after that age you start slowing down mentally. Modern protection methods are like whiskey, when you are going to try a hard move; you put a nut in.

I would certainly not have been able to make the moves today which I did in 1955, regardless of how hard they are. Until your middle thirties your muscular ability is still good, but after that age, your peak performance begins to drop off, though your stamina might improve. Yet with the aid of the new protection devices you can still make such hard moves, which can only mean in your earlier days you were climbing well below your top standard. The margins of safety then meant that one needed to rely on having good technique, and not to be bolstered by rope work and modern protection. My climbs of today are a lot easier to pioneer, and mentally they only take me one tenth of the effort they once did. It has been years since I was frightened that I was going to be killed.

D.G. You have always been the absolute amateur, climbing mainly at weekends and during short summer holidays. Have you ever been envious of climbers like Bonington and Brown who have managed to spend so much of their time climbing. Do you think that professionalism with its inevitable train of commercialism will in the end be a very bad thing for the future of climbing?

A.A. I think professionalism is bad for climbing. Climbing is essentially a pastime and not a competitive activity; hence the more that professionalism develops the worse it is for our sport. Am I envious? If I had my time over again I would most certainly spend four years at a University, doing a subject that involves the minimum amount of work, and a maximum of spare time. Expeditions-no I am not interested in. The effort involved seems to me to be so great I do not think I would enjoy it. The pinnacle of my desire would be a three- month holiday in the Alps.

D.G. Do you think that you ever give up climbing?

A.A. I hope that I will always climb. I cannot say whether that will always be so. I will find it difficult to drop my standard, but I ought to be leaving a lot of easier routes to climb in the years to come. I think I will always climb. I hope to be like some of the old Fell and Rock Club members, like the present President on his meet at 65 years of age. Borrowing a pair of rock boots to be taken up some Very Severes-that is how I hope I will be at 65, borrowing somebody else’s magic boots and being led up an Extreme climb.

D.G. Many thanks Allan. I think we need to enlighten a new generation of climbers as to why ‘Ragman’s Trumpet’ was in your case so apposite, for your weekdays are spent working in the family business, as wool waste merchants (Once a traditional historical activity in Bradford?)

Update: In later life Allan due to injury turned away from climbing to sailing and his family opened an outdoor retail shop in Bradford, using his name as the identifier. Brian Evans was a founder along with Walt Unsworth of the Cicerone Press, which they sold on at their retirement.

Dennis Gray: 1973